François-René de Chateaubriand

Pronunciation:

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, was born in Saint-Malo on September 4, 1768, on a stormy night, into a Breton family of former nobility, who had regained a certain financial ease thanks to the business acumen of his father, a shipowner.

His early years were those of a child abandoned to servants. From the age of nine, he spent his childhood at the Château de Combourg , which his father bought in 1771.

Renouncing the career as a sailor that seemed promised to him, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1786, and became involved in the life of the Parisian salons. Forced to emigrate in April 1791, he chose the fledgling United States of America as his land of exile, spending time in Baltimore and Philadelphia, visiting Niagara Falls and even living among the Indians.

Returning from the New World in 1792, he joined the emigrant army in Coblence, and fought under Frédéric-Louis de Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen against the army of the French Republic. Wounded at the siege of Thionville, he went to Brussels, then Jersey, and finally London, where he settled in 1793, living poorly on a few French translations and lessons, and working at night on his Essay on Revolutions, published in 1797.

Chateaubriand returned to France in May 1800. After being struck off the list of émigrés, he became involved in literary life, editing the Mercure de France magazine with his friend Jean-Pierre Louis de Fontanes, and bringing out Atala, an exotic novel and Christian tragedy which met with resounding success, in 1801, followed in 1802 by René, ou les Effets des passions and the Génie du christianisme, which celebrated Christian morality, inaugurating a return to the religious after the Revolution.

In 1803, François-René de Chateaubriand embarked on a diplomatic career, being appointed by the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte to accompany Cardinal Fesch to Rome as first secretary to the embassy. The following year, he was appointed to represent France to the Republic of Valais. It was there that Chateaubriand learned of the execution of the Duc d'Enghien, prompting his immediate resignation and resolute opposition to the First Consul and, a few months later, to the Emperor.

In 1806, he embarked for the Orient, visiting Greece, Asia Minor, Palestine and returning via Egypt, Tunisia and Spain, a journey that would provide him with the material for his Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem five years later. On his return in 1807, exiled by Napoleon three leagues from the capital, he moved to La Vallée-aux-Loups, near Sceaux, where he wrote Les Martyrs.

In 1811, Chateaubriand was elected to Marie-Joseph Chénier's seat in the Académie française; but Napoleon did not allow him to deliver the acceptance speech he had written for the occasion, which was too critical of the Revolution and imperial tyranny; the writer would have to wait until the Restoration to take his seat among the Immortals.

He enthusiastically welcomed the Emperor's abdication, publishing his pamphlet De Buonaparte et des Bourbons on March 30, 1814, which King Louis XVIII said served him as well as a hundred thousand men. Louis XVIII rewarded him by appointing him ambassador to Sweden, but the Emperor's return caught them unawares, and Chateaubriand spent the Hundred Days with his monarch in Ghent, becoming a member of his cabinet. On this occasion, he wrote a Rapport sur l'état de la France.

On June 18, 1815, he heard with pain the cannonade of Waterloo; a drama played out in his soul, torn between patriotism and loyalty: What was this battle? Was it definitive? Was Napoleon there in person? Was the world, like Christ's robe, thrown into the fray? Success or defeat for one army or the other, what would be the consequence of the event for the peoples, freedom or slavery? But what blood was flowing! Wasn't every sound that reached my ears the last gasp of a Frenchman? Was this a new Crécy, a new Poitiers, a new Azincourt, to be enjoyed by France's most implacable enemies? If they triumphed, was not our glory lost? If Napoleon won, what would become of our freedom? Although Napoleon's success would mean eternal exile for me, the fatherland prevailed in my heart at that moment; my wishes were for France's oppressor, if he were to save our honor and wrest us from foreign domination. Was Wellington triumphant? Legitimacy would return to Paris behind the red uniforms that had just dyed their crimson with the blood of the French! The carriages of royalty's coronation would be the ambulance wagons filled with our mutilated grenadiers! What would a restoration accomplished under such auspices be? These were just a few of the ideas that tormented me. Every cannon shot gave me a jolt and doubled my heartbeat. A few leagues away from an immense catastrophe, I couldn't see it; I couldn't touch the vast funeral monument growing by the minute at Waterloo, just as from the shore of Boulaq, on the banks of the Nile, I stretched out my hands in vain towards the Pyramids.

A member of the Chamber of Peers after Napoleon's second abdication, Chateaubriand voted for Michel NeyMarshal Ney's death. Briefly Minister of State, he lost the post the following year and became a spearhead of the ultra-royalist opposition.

His diplomatic and political career reached its peak in the years that followed: in 1821, he was appointed French Minister in Berlin, then Ambassador in London, plenipotentiary representative of France at the Congress of Verona in 1822, and finally Minister of Foreign Affairs. In 1823, he organized the Spanish expedition to re-establish the sovereignty of Ferdinand VII, seeing it as an opportunity to restore France's position as a great power. The campaign, under the command of the Duc d'Angoulême and featuring some of Napoleon's former senior officers (Marshals Bon-Adrien Jannot de Moncey and Charles Oudinot, Generals Gabriel Molitor and Étienne Tardif de Pommeroux de Bordesoulle), was a resounding success. Chateaubriand's pride in this success aroused such jealousy that in 1824, following a disagreement with the President of the Council, Joseph de Villèle, he lost his portfolio. After Villèle's fall, he was appointed ambassador to Rome in 1828, but resigned with the advent of the Jules de Polignac ministry.

He withdrew from politics for good under the July Monarchy, and had harsh words for Louis-Philippe I (As for me, a republican by nature, a monarchist by reason, and a Bourbonnist by honor, I would have been much better off with a democracy, if I had not been able to preserve the legitimate monarchy, than with the bastard monarchy granted by I don't know who

). He devoted himself to completing his memoirs, a monumental work begun in 1811 and scheduled for publication half a century after his death. However, financial problems prevented this, and the Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe, for which he signed over the rights in 1836, was published the day after his death.

François-René de Chateaubriand died in Paris on July 4, 1848. In accordance with his wishes, he was buried on the Grand Bé , an uninhabited islet at the foot of the Saint-Malo ramparts.

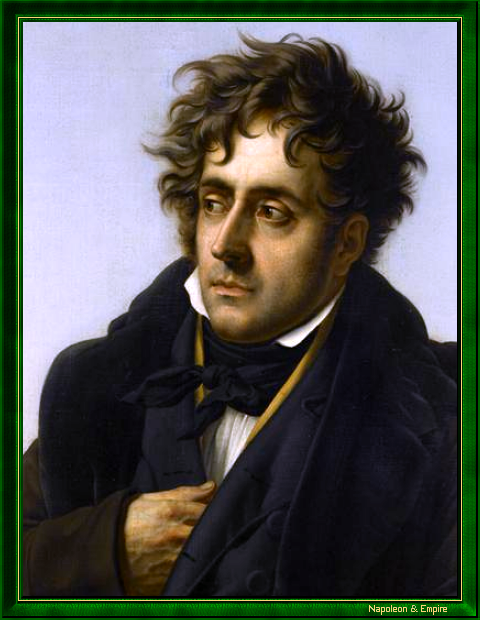

"François-René de Chateaubriand méditant sur les ruines de Rome" (détail), painted circa 1808 by Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (Montargis 1767 - Paris 1824).

A full-length statue of Chateaubriand honors his memory in his hometown, and another , in granite, by Alphonse Camille Terroir, stands on the town square in Combourg, in front of the château.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord said of Chateaubriand:Monsieur de Chateaubriand believes he is going deaf because he no longer hears people talking about him, while Chateaubriand described the Prince of Benevento as follows:

His eyes were dull, so that one could hardly read in them, which served him well; as he had received much contempt, he had absorbed it, and he had placed it in the two hanging corners of his mouth.

Philately: François-René de Chateaubriand has been the subject of several philatelic issues:

- In 1948, the Post Office of the French Republic issued an 18 F stamp bearing his effigy ;

- The Post Office of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon did the same in 1968 with a 10 F stamp ;

- The same year, the postal services of Monaco issued a 0.10 F stamp and five others dedicated to his main literary works;

- The Emirate of Fujaïrah, a major philatelic issuer during its short autonomous existence, chose Chateaubriand to illustrate the sign of Virgo in a series devoted to the signs of the Zodiac, with a 50 Dirham stamp .

Banknotes: The Banque de France also paid tribute to Chateaubriand, with a 500 F banknote issued from 1945 onwards.

Address

5, Rue de Beaune. Paris VIIème arrondissement

This is where Chateubriand stayed in 1804.7, Rue du Regard. Paris VIème arrondissement

Hôtel de Beaune, where François-René de Chateaubriand resided in 1825-1826. Marshal Victor, Duke of Bellune, lived there from 1830 until his death in 1841.27, Rue Saint-Dominique. Paris VIIème arrondissement

Another Parisian address of the Viscount.120, Rue du Bac. Paris VIIème arrondissement

Hôtel de Clermont-Tonnerre, where Chateaubriand lived from 1838 until his death in 1848.Other portraits

"Portrait de Chateaubriand sur fond de paysage montagneux", by Paulin Guérin (1783-1855), sometimes attributed to Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774-1833).

"François-René de Chateaubriand" by Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (Montargis 1767 - Paris 1824).

"Chateaubriand en costume de pair de France", painted in 1828 by Pierre-Louis Delaval (Paris 1790 - Paris 1870).