Napoleon and the United States of America

First contact. Restoration of harmony with the United States [1]

Upon assuming power in November 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte inherited a considerably deteriorated situation between France and the United States. What has been dubbed a "quasi-war" had pitted them against each other since 1798. This was a simmering naval conflict stemming from the Americans' refusal to pay the debts owed to Republican France by the French of the Ancien Régime. Adding to this grievance was the growing alliance between the government in Washington and the United Kingdom.

Napoleon, as First Consul, quickly realized the need to resolve this dispute. Prolonging it could lead to an alliance between the United States and the United Kingdom. The consequences would undoubtedly be disastrous for France. Ending the discord, on the other hand, would allow the ships involved in this dispute to be redeployed to the war against England.

Furthermore, the dire state of French trade also argued in favor of this reconciliation. Regained access to the American and Caribbean markets would offer it the opportunity to emerge from its slump.

These combined considerations dictated the conduct of the new French authorities. They decided to accept the concessions necessary to achieve détente. They also did not shy away from gestures of goodwill. Thus, the French army went into mourning upon the announcement of George Washington's death.

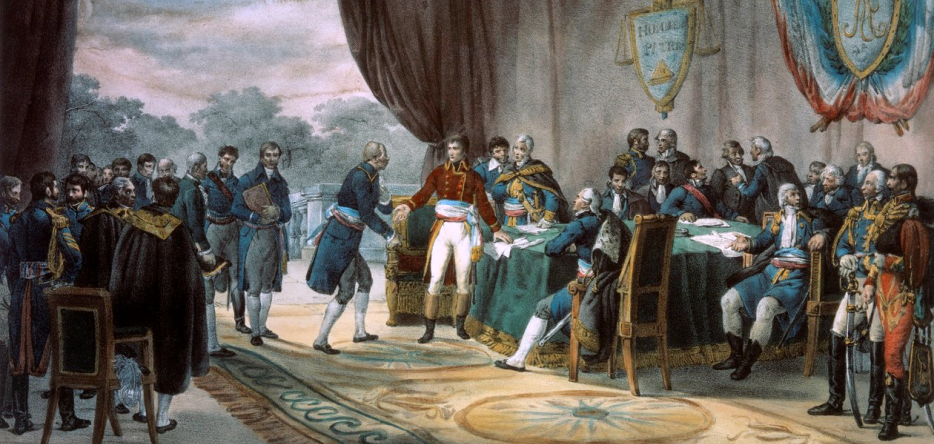

The Treaty of Mortefontaine, signed on September 30, 1800, culminated this policy after eight months of negotiations. It guaranteed American shipowners compensation for the loss of their ships and cargoes. Both parties also agreed on the restitution of seized property and the re-establishment of trade and diplomatic relations.

News of this agreement reached the United States soon after the presidential election, which saw the triumph of Thomas Jefferson, an avowed Francophile. Despite this reputation, he remained faithful to the doctrine defined by George Washington in matters of foreign affairs: to stay out of disputes between European powers.

Failure of French ambitions in North America and the Caribbean

Louisiana Purchase [2]

Between 1800 and 1803 , the First Consul pursued a policy of restoring the French colonial empire in the New World. This resulted, among other things, in the signing of the Treaty of San Ildefonso with Spain. This treaty ceded Louisiana and the right bank of the Mississippi River to France. Sealed the day after the Treaty of Mortefontaine, it was kept secret for as long as possible. The French authorities knew how irritated their American counterparts would be by this agreement. It thwarted their own ambitions in the region. It replaced a former neighbor, considered weak, peaceful, and easy to manipulate, with a new one that was powerful, ambitious, and restless.

And indeed, Congress erupted in anger when the news reached it. Some of its members demanded war against France. Jefferson, more clear-headed, knew that his armed forces could not withstand such a confrontation. In January 1803, he dispatched an ambassador extraordinary, James Monroe , to Paris. His mission was to purchase Louisiana.

By this time, France's ambitions in this part of the world were already moribund. Its Caribbean possessions were slipping from its grasp. A revolt had broken out in Guadeloupe island, and Saint-Domingue had been ravaged by civil war for ten years. Worse still, the expeditionary force dispatched there by the First Consul under the command of his own brother-in-law, General Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc, had failed. Despite the capture of Toussaint Louverture, France had not regained lasting control of the island.

News of Leclerc's death reached France in early 1803. Based on the accompanying reports, the French government deemed the loss of Saint-Domingue inevitable. It ceased sending reinforcements to General Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Rochambeau , Leclerc's successor, who would capitulate in November 1803. The foothold essential to its American expansion had definitively slipped from France's grasp.

Napoleon Bonaparte abandoned his transatlantic ambitions as early as March 1803 and immediately and radically altered his North American policy. The United States ambassador, Robert R. Livingston , was offered Louisiana. Negotiations were already underway between him and the French Minister of the Treasury, François de Barbé-Marbois, when Jefferson's emissaries arrived in Paris. On April 30, 1803, the deal was finalized for 80 million francs (15 million dollars at the time) : 60 million for France and 20 million for the citizens of the United States penalized by the "quasi-war." Thus took place the most colossal real estate transaction in history: 220 million hectares (828,000 square miles) changed hands.

This sale received little attention in France. In the United States, however, it strengthened the resolve of those who wanted to extend the federation to all of North America. They would one day formalize their doctrine under the title "Manifest Destiny". In the meantime, as early as 1804, Jefferson sent explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to survey and map these new territories and those separating them from the Pacific Ocean.

A point of contention: the Continental Blockade [3]

Relations between France and the United States deteriorated in the following years. The proclamation of the Empire shocked the Americans, President Jefferson in particular. Above all, the Continental System, a consequence of the Anglo-French struggle, hampered the young american republic's commercial interests. Moreover, its protests and its ambassadors were met with disdain, even insolence, from imperial diplomacy — similar in this respect to that of the United Kingdom.

Jefferson reacted by signing the Embargo Act, which closed US ports to foreign trade. The measure proved disastrous. His successor, James Madison, mitigated it by restricting its scope to France and England. In late 1811, Napoleon relaxed the rules affecting trade with neutral countries, particularly the Americans. He believed they were on the verge of going to war with Great Britain, which would force the latter to fight on two fronts. This conflict did indeed break out on June 18, 1812, but it was already too late for Napoleon to gain an advantage. The dispute ended in December 1814 without having affected the fate of Europe.

An inaccessible land of asylum [4] [5] [6] [7]

All the accounts of Napoleon's close associates (Emmanuel de Las Cases , Gaspard Gourgaud, René Savary, Charles Tristan de Montholon ) confirmed Napoleon's intention to go into exile in the USA after his second abdication, on June 22, 1815.

Article 1 of a decree from the government commission, dated June 26 and signed by Joseph Fouché, formally attested to this. This was also the opinion of the British Admiralty, expressed in instructions transmitted by Vice-Admiral Henry Hotham to the captain of the HMS Bellerophon, Frederick Lewis Maitland , on July 10. Finally, Napoleon's directives to Gourgaud expressly mentionned it.

Napoleon left La Malmaison [48.87080, 2.16685] on June 29, 1815. On July 3, he arrived in Rochefort [45.93701, -0.95807]. The provisional government had placed two frigates, the Medusa and the Saale, at his disposal for his passage to the United States. American ships, as well as French merchant vessels, all present in the harbor, also offered to welcome him.

The former Emperor stayed in the city from July 3rd to 8th, before boarding a frigate, the Saale. He then took up residence on the Île d'Aix [46.01305, -1.17458] until the 15th, still awaiting the English safe-conducts that Fouché had promised him.

In their absence — Captain Maitland made this very clear to Savary, Las Cases, and Lallemand, who had come to sound him out — the frigates would be attacked, the French ships seized, and the American vessels boarded. In any case, Napoleon risked being taken prisoner.

During this period, several proposals for clandestine passage to America were submitted to the deposed monarch:

- The first suggestion came from a French naval lieutenant, Jean-Victor Besson, commander of the Danish merchant brig La Magdalena, which was transporting brandy; two empty barrels were prepared to serve as hiding places in case of inspection by the English. This solution seemed to tempt Napoleon for a time, but he abandoned it on July 13.

- A second one came from naval cadets named Gentil, Duret, Pottier, Salis, and Châteauneuf [8]. They suggested using a chasse-marée (a type of very fast fishing boat). Their enthusiasm quickly cooled in the face of the difficulties of the undertaking.

- The third option was to join a corvette, La Bayadère, in the roadstead of Bordeaux, while the frigates would attract the attention of the English cruiser elsewhere.

When Napoleon finally decided to break the blockade aboard the Saale, her captain, Pierre-Henri Philibert , refused, hiding behind orders from the French provisional government.

Since Napoleon did not want to use an American vessel (two fast merchant ships, the Ludlow and the Pike, were ready to depart for New York) and clandestine crossings seemed impossible, he resigned himself to going to England. His entourage, however, did not give up hope that this was merely a stepping stone to the Americas.

We know what happened next.

A breeding ground for escape projects

Between 1817 and 1821, admirers and former soldiers of the Emperor drew up to his benefit, but without his consent, half a dozen escape plans from the island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic [-15.95013, -5.683 07]. Some were hatched on American soil and undoubtedly aimed to repatriate the glorious exile. Most involved French refugees in the United States, some of them quite famous.

Here are a few examples:

- One was directed by Joseph Lakanal and Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes, the president of the "Vine and Olive Colony" (Alabama) [32.52042, -87.84088]. They devised a plan to have Joseph Bonaparte proclaimed King of Mexico, a Spanish viceroyalty then in the throes of independence movements, as a springboard for an expedition to Saint Helena in 1817. But Joseph's lack of enthusiasm and Spain's temporary reassertion of control over Mexico caused this plan to fail.

- Another operation was possibly conceived by the brothers François Antoine "Charles" and Henri Dominique Lallemand, two Napoleonic generals stationed in the Champ d'Asile colony in Texas [towards 29.93787, -94.77080], along with one hundred and twenty Bonapartist officers. It benefited from the support of the buccaneer Jean Lafitte , famous for having successfully defended New Orleans against the British in 1815. But the destruction of the colony by the Spanish in October 1818 brought it to an end.

- The final attempt was by Nicolas (or Nicholas) Girod , a Savoyard who had emigrated to New Orleans, where he had served as mayor from 1812 to 1815. In 1821, he had a house he owned renovated and furnished at the corner of Saint-Louis and Chartres streets [since known as the Napoleon House] [29.95592, -90.06508] to accommodate Napoleon, whom he planned to help escape from Saint Helena. He had a clipper ship, the Seraphine, built and armed in Charleston. She was about to set sail under the command of the Louisiana pirate Dominique Yon (Lafitte's right-hand man) when the crew of a French merchant ship brought news of Napoleon's death, which had occurred on May 5, 1821.

The other Bonapartes in the United States

Napoleon, therefore, never actually set foot in the USA, a fate mirrored by his younger brother Lucien. The latter did indeed plan to settle there in 1810 , but was intercepted by the British during his transatlantic voyage. Other members of his family fared better:

- Their elder brother Joseph spent two extended periods in the United States, under the name Count de Survilliers. The first one, from August 1815 to 1832, saw him reside for a few months in Philadelphia after arriving in New York, then in 1817 he acquired the Point Breeze estate in Bordentown, New Jersey, on the banks of the Delaware River [40.15611, -74.70833]. After three years in England, he returned to the United States in 1836 and remained there until November 1839, when he finally returned to Europe..

- The youngest of the siblings, Jérôme, visited the USA in 1803 and even married Elizabeth Patterson , daughter of a wealthy Baltimore merchant, in a ceremony officiated by John Carroll , Archbishop of Baltimore, on December 24, 1803. Their honeymoon to Niagara Falls was one of the first recorded in that location.

- Two of Napoleon's nephews, Achille and Lucien Murat, children of his sister Caroline and Joachim Murat, emigrated in 1822 and 1824 respectively.

Jérôme Bonaparte's American romance ensured he had descendants, some of whom went on to have brilliant careers. For example, Charles Joseph Bonaparte , Jérôme's grandson, was Secretary of the Navy and later Attorney General under President Theodore Roosevelt. The United States owes to him the creation, in 1908, of the Bureau of Investigation, the precursor to the FBI.

Bibliographical references

- BERTRAND, Henri Gatien. Cahiers de Sainte-Hélène - Les 500 derniers jours (1820-1821). Paris : Perrin, 2021. (La Bibliothèque de Sainte-Hélène). EAN 978-2-262-09532-1

- GOURGAUD, Gaspard. Sainte-Hélène - Journal inédit de 1815 à 1818. s.l. LACF sas, 2009. 2 vol. ISBN 9782354980351.

- LAS CASES, Emmanuel. Le Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène. s.l. Gallimard, 1956. 2 vol. (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade)

- MARCHAND, Louis-Joseph. Mémoires. Paris : Tallandier, 2003. 800 p. ISBN 978-2847340778.

- PAGÉ, Sylvain. L'Amérique du Nord et Napoléon. Paris : Nouveau monde éditions / Fondation Napoléon, 2003. 208 p. (La Bibliothèque Napoléon, Etudes). ISBN 2-84736-030-1.

- SAVARY, Anne Jean Marie René, duc de Rovigo. Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de l'Empereur. Pont-Authou : Les éditions d'Héligoland, 2010. 7 vol. ISBN 978-2-914874-75-5

Notes

01. - PAGÉ, 2003 ↑02. - PAGÉ, 2003 ↑

03. - PAGÉ, 2003 ↑

04. - BERTRAND, 2021 ↑

05. - GOURGAUD, 2009 ↑

06. - LAS CASES, 1956 ↑

07. - SAVARY, 2010 ↑

08. - MARCHAND, 2003 ↑