Antoine Augustin Parmentier

Baron of the Empire

Pronunciation:

Antoine Augustin Parmentier was born on August 12, 1737. His father died at an early age, and it was his mother who taught him his first rudiments of Latin. At 13, he was placed as a pupil with a pharmacist in Montdidier. At 18, he moved to Paris to join a relative who was also a pharmacist. A brilliant student, he soon acquired remarkable scientific knowledge.

In 1757, he left as an apothecary for the Hanover army, working under Bayen, a pharmacist himself, who quickly befriended him. At the age of 24, he was commissioned as the army's second pharmacist. During the Hanover War, the young man won the confidence of all and kept up the courage of the other pharmacists during an epidemic that struck the hospitals. He manages to stop it. Captured five times by the Prussians, he was taken to a fortress and kept there as a prisoner. There, he was fed only potatoes, which were considered degrading food. Parmentier was quick to see the nutritional virtues of potatoes. It was against this backdrop that he decided to promote the plant [1].

Once free, Parmentier went to Frankfurt and lived for a while with Meyer, a renowned German chemist, but soon missed his homeland. He returned to Paris in 1763. There, he studied physics with Nollet, chemistry with Rouelle and botany with Jussieu. He worked hard, spending every last penny he had to buy books. On October 16, 1766, he passed the competitive examination to become a master apothecary at Les Invalides [2]. He remained in this position for six years, cultivating a small garden and experimenting with plants to improve their nutritional properties. He then became a master pharmacist. Seduced by the scientist, the governor of the Invalides, Baron d'Espagnac, created a post for him as apothecary-major of the French Armies, head of the pharmacy of the Invalides, on July 18, 1772. Despite this, the Sisters, not wanting to be dispossessed, had him dismissed on December 31, 1774 [3].

In 1772, he had won a prize from the Académie de Besançon for a dissertation praising the potato as a foodstuff. In 1774, free of all commitments, he was able to devote himself to his research. In 1773, he published a book entitled Examen chimique des pommes de terre, in which he discussed the constituents of wheat and rice. In 1774, he produced Model's Récréations physiques. Two resounding works that put him on the map. In 1774, he was promoted to royal censor and given the task of visiting various regions to determine why bread was so poorly made. That year, in response, he published a brochure entitled Méthode facile pour conserver à peu de frais les grains et les farines. Visiting his home town of Montdidier, his fellow citizens brought him the problem of wheat decay, which was ravaging the surrounding fields. After chemical studies, he determined the nature of the problem and recorded his findings in a paper read at the Royal Society of Medicine in 1776, Analyse de la carie du froment (Analysis of wheat decay). In 1777, his Avis aux bonnes ménagères des villes et des campagnes sur la meilleure manière de faire le pain (Advice to good housewives in town and country on the best way to bake bread) was published to enormous acclaim, turning the rural and urban economy upside down [4]. That same year, he took up a position at the Collège de pharmacie as a demonstrator in botany and natural history [5]. This was followed in 1778 by Le Parfait boulanger (The Perfect Baker). Other works on other dishes were also written.

On June 8, 1780, a bakery school was founded in Paris. Parmentier was one of its teachers. He continued to write books on a wide variety of subjects. In 1782, he was approached to take up the position of chemist to the German monarch. He declined. In 1784, his dissertation on the use of corn in the south of France won a prize from the Bordeaux Academy. This memoir was reprinted in 1812 at the expense of the Empire, and helped to perfect the cultivation of the starch [6].

In 1787, King Louis XVI entrusted him with 54 acres of land to cultivate. During the day, soldiers guarded the land, and at night, Parmentier let the poor people steal potato plants to grow for their own needs. In 1789, his Traité sur la culture et les usages de la pomme de terre, de la patate et du topinambour was printed by order of Louis XVI. Parmentier had succeeded. The potato was cultivated throughout France [7].

In 1790, Parmentier and Nicolas Deyeux, another pharmacist, won a prize from the Royal Society of Medicine for their memoir detailing their chemical study of milk. In 1791, the two men again won the prize for their analysis of blood, the title of the dissertation they presented to the institution [8].

When the Revolution broke out, Parmentier lost everything. He was even seriously vilified and threatened by the new regime, but he was sent to the south of France to gather as many medicines as possible to equip military pharmacies. After a while, however, his services to humanity were finally recognized. In 1793, the College of Pharmacy was dissolved. In 1796, pharmacists formed the Société des pharmaciens de Paris. This society provided free education, recognized by the Directoire as being of public utility in 1797 [9].

In 1795, he was chief pharmacist, president of the Paris health council, member of the army health commission, of the subsistence and supplies commission, and of the general administration of the capital's civil hospices. In association with Bayen, he also published his Formulaire pharmaceutique, which was also translated into Italian and reprinted several times. When Bayen died in 1798, he remained the sole Inspector General of military pharmacies. In 1802, he popularized his work co-written with Bayen, newly entitled Code pharmaceutique à l'usage des hospices civils. It was a colossal success, reprinted four times (1803, 1807, 1811 and 1818) [10].

The first vaccination experiments were carried out at his home. From then on, he fought for vaccinia to be inoculated into the poorest of the poor, and for inoculation centers to be set up in every département. His memoirs on hospital salubrity, soldier's bread, water as a beverage for troops, etc. earned him membership of the Institut de France, physical and mathematical sciences section, on December 13, 1795 [11].

In 1800, he helped found the Ecole de Boulangerie in France [12].

On December 15, 1803, the First Consul confirmed him as Inspector General of the Health Service. He had held this position since 1796, and remained in it until his death in 1813. By decree, Bonaparte also had him appointed first army pharmacist in 1800. The future emperor had great confidence in Antoine Augustin [13].

That same year, he became president of the Société de pharmacie de Paris, to which he had made a major contribution. In 1803, the Paris School of Pharmacy opened its doors [14]. In 1804, he became the first Army Pharmacist for the Ocean Coast Army, and in 1805, he was put in charge of supplying the hospitals of the Grande Armée.

When Napoleon introduced the Legion of Honor, he issued a decree awarding 10 crosses of the Legion of Honor for civil and military service in pharmacy. Everyone was astonished that Parmentier didn't receive it. It soon became known that Parmentier was the one who had devised the list. He was immediately awarded an eleventh medal. He was elevated to the rank of Officier de la Légion d'Honneur [15]. His knowledge was immense, but his humility was also proverbial. Parmentier was a loyal admirer of Napoleon. A fierce believer in prevention, he was convinced that appropriate dietary and medical measures could only be taken with strong government intervention. For Parmentier, the Emperor was the right man for the job [16].

With the continental blockade, sugar had become a rare, unaffordable commodity. From 1808 to 1813, to compensate for this shortage, he studied grapes and vines, carrying out numerous experiments and writing numerous memoirs on the subject. In 1810, in association with Jean-Antoine Chaptal, he defined a technique for extracting sugar from grapes. However, the cultivation of sugar beet rendered his research futile. Throughout this period of famine for the French people, Parmentier was their food provider. He struggled to find solutions. He researched wine and flour preservation, cold storage, meat refrigeration and the use of dairy products. He took part in the development of boiling preserves. He was a pioneer in all areas of the food industry [17].

From 1805 to 1813, together with physicians Philippe Pinel and Joseph Guillotin, he played an active role in the smallpox vaccination campaigns launched in 1799, with the support of General Bonaparte [18].

Suffering from pulmonary phthisis, he died on December 17, 1813. He never married. He is buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, in the 39th division, 2nd row, P, 26 [19] .

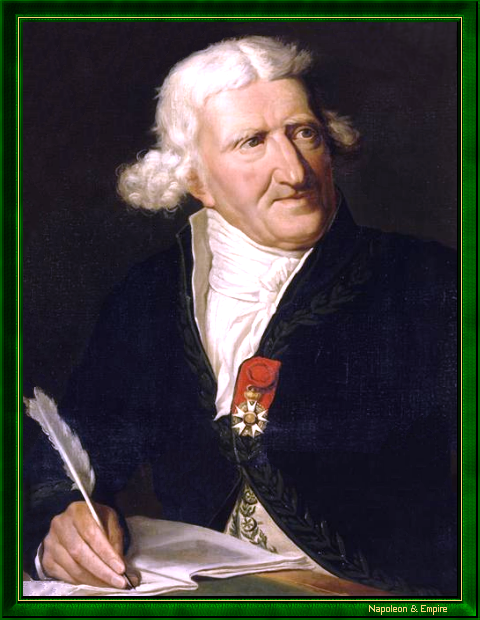

"Baron Antoine Parmentier", by Hippolyte-Isodore Dupuis-Colson (1820-1862).

At least 48 diplomas are said to have been awarded to him during his lifetime. The Academies of Alexandria, Berne, Brussels, Florence, Geneva, Lausanne, Madrid and Milan, Naples, Turin and Vienna count him among their members. He left behind some 165 works on agronomy [20].

In addition, Parmentier published numerous articles, memoirs and dissertations in scientific journals such as Rosier's Cours complet d'agriculture, Bibliothèque physico-économique, Journal de physique, Mémoires de la Société royale d'agriculture, Encyclopédie méthodique, Feuille du cultivateur, Journal de la Société de pharmacie de Paris, Annales de chimie, le Journal et le Bulletin de pharmacie, le Magasin encyclopédique, le Bulletin de la Société philomathique, les Mémoires des Sociétés savantes et littéraires de la république française, le Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, le Théâtre d'agriculture d'Olivier de Serres, le Nouveau cours d'agriculture and le Recueil de l'Institut national, to name but a few [21].

In his advice to his young colleagues under his command, Parmentier asserts: My friends, pharmacy demands, more than any other profession, gravity in morals, wisdom in conduct, great docility to the advice of experience, a love of order and a sedentary life, severity of principle and inflexible probity. Be honest men; virtue alone makes us happy and leads us to want others to become so; strive to obtain, by your frankness, your probity and your science, a personal consideration, independent of your title, at the same time as you determine, by your fairness and your gentleness, your subordinates to love and respect you

. [22] Need I say more about Parmentier? Grateful French society has named streets and schools after him, and erected statues and other tributes.

Acknowledgments

This biographical notice was written by Mr. Xavier Riaud, Doctor of Dental Surgery, Doctor of Epistemology, History of Science and Technology, Laureate and national associate member of the National Academy of Dental Surgery, Medal of Honor of the International Napoleonic Society, and posted online with his kind permission.The translation and any errors it may contain are the responsibility of Napoleon & Empire

Bibliographical references for this entry

• BLAESSINGER Edmond, Quelques grandes figures de la pharmacie militaire, Baillère (ed.), Paris, 1948.

• DE BEAUVILLÉ Victor, Histoire de Montdidier, Livre IV - Chapitre II - Section LIV, https://santerre.baillet.org, 2010, pp. 1-21.

• FOUGÈRE Paule, Grands pharmaciens, Buchet/Castel (ed.), Paris, 1956.

• https://fr.wikipedia.org, Antoine Parmentier, 2010, pp. 1-6.

• https://www.appl-lachaise.net, Parmentier Antoine Augustin (1737-1813), 2005, pp. 1-2.

• GOURDOL Jean-Yves, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier (1737-1813), pharmacien des Armées, vulgarisateur de la pomme de terre, in http://www.medarus.org, 2010, pp. 1-4.

• https://www.shp-asso.org, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier (1737-1813), no date, p. 1.

• MEYLEMANS R., Les grands noms de l'Empire, in Ambulance 1809 de la Garde impériale, http://ambulance1809-gardeimperiale.ibelgique.com, 2010, pp. 1-22.

• MURATORI-PHILIPPE Anne, Parmentier, Plon (ed.), Paris, 2006.

• Riaud Xavier, Chirurgiens, médecins ou pharmaciens nobles d'Empire et/ou titulaires de la Légion d'honneur, in The International Napoleonic Society, Montreal, 2010, http://www.napoleonicsociety.com, pp. 1-5.

Notes

01. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; FOUGÈRE, 1956 ; MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑02. - GOURDOL, 2010 ↑

03. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; BLAESSINGER, 1948 ↑

04. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; BLAESSINGER, 1948 ↑

05. - GOURDOL, 2010 ↑

06. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; FOUGÈRE, 1956 ; MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑

07. - https://fr.wikipedia.org, 2010 ↑

08. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; BLAESSINGER, 1948 ↑

09. - GOURDOL, 2010 ; FOUGÈRE, 1956 ↑

10. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; GOURDOL, 2010 ; MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑

11. - MEYLEMANS, 2010 ↑

12. - GOURDOL, 2010 ↑

13. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; GOURDOL, 2010 ; MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑

14. - GOURDOL, 2010 ↑

15. - Riaud, 2010 ↑

16. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑

17. - GOURDOL, 2010 ; DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ; BLAESSINGER, 1948 ↑

18. - GOURDOL, 2010 ↑

19. - https://www.appl-lachaise.net, 2005 ↑

20. - https://www.shp-asso.org, sans date ↑

21. - MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ↑

22. - MURATORI-PHILIPPE, 2006 ; DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ↑

23. - DE BEAUVILLÉ, 2010 ↑

Address

68, Rue du Chemin Vert. Paris XIème arrondissement

It was at this address (then 12 Rue des Amandiers) that Parmentier lived at the time of his death in 1813.Other portraits

"Antoine, Baron Parmentier" painted in 1812 by François Dumont the Elder (1751-1831).