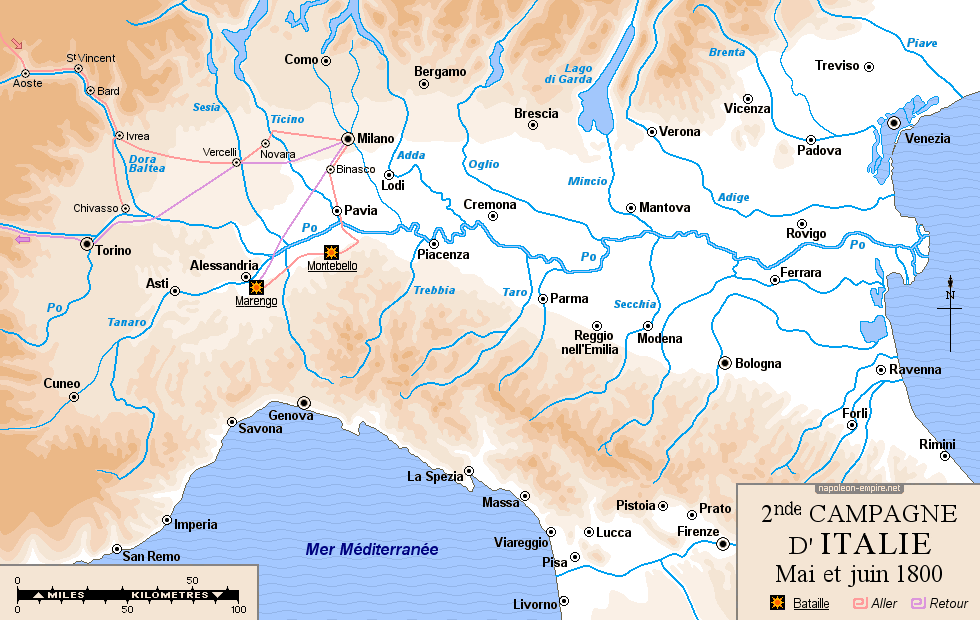

Military operations of the second Italian Campaign (1800)

When he seized power on 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (November 9, 1799), Napoleon Bonaparte inherited a stabilized military situation. The dangers faced by France during 1799 had been averted by the victories of Andréa Masséna in Switzerland and Guillaume Brune in Holland. Nevertheless, the Second Coalition remained a threat.

The Austrians indeed had a large number of troops in Italy and Germany:

- in the Po Valley, General Michael von Melas's army numbered 130,000 men;

- in the Danube [Die Donau] Valley, Archduke Charles of Austria, and later Feldzeugmeister Pál Kray von Krajova und Topolya , commanded another 120,000.

Facing them, France deployed:

- in the north, retreating to the left bank of the river, the 150,000 soldiers of the Army of the Rhine under Jean Victor Marie Moreau;

- in the south, pushed back to Genoa [Genova] and the Riviera, the 40,000 troops of the Army of Italy under André Masséna.

These forces, separated by the Alps and Switzerland, were further undermined by indiscipline, desertion, and inadequate supplies.

Creation of the Reserve Army

Very quickly, as early as 14 Frimaire, Year VIII (December 5, 1799), the First Consul ordered the creation of a Reserve Corps, which he intended to position at the heart of the French defenses. Positioned in this way, this unit would monitor Switzerland—recently brought under French control—and would be able to reinforce either flank as needed.

Planned to number 40,000 men, this formation was slowly assembled. Its troops were drawn from Brittany and the Vendée, where pacification was complete, from the Army of Italy, and from the depots of the Army of the Orient. The artillery assembled at Auxonne , the cavalry at Dole; the infantry was distributed between Dijon, Saulieu, Beaune, and Bourg-en-Bresse.

In April 1800, Alexandre Berthier received the theoretical command of this so-called Reserve Army. The First Consul had, in fact, preferred to refrain from officially taking command, both so as not to alarm the fastidious republicans and to preserve the essentially civilian nature of his role. In May, when Bonaparte entered Switzerland, 36,000 troops followed him.

Initial Operational Plan

The operational plan initially assigned the main task to the Army of the Rhine, as peace could only be won in Germany. Bonaparte even intended to go there first to oversee the offensive. While allowing Moreau to remain in command, he would reserve for himself the role of commander-in-chief, as he alone could enforce the strict cooperation essential between the three armies (the Army of the Rhine, the Army of Italy, and the Reserve Army).

The planned maneuver also demanded speed and audacity, whereas Moreau's reputation rested primarily on his prudence. For the First Consul, being on the ground thus seemed of paramount importance in order to inject the necessary momentum for victory.

Moreau's Objections

But Moreau refused both to be placed under Bonaparte's command and to implement the plan he had devised. Following extensive negotiations in Paris between Jean-Joseph Dessolles , his chief of staff, the First Consul, and the Minister of War, Lazare Carnot, Moreau obtained, in writing, the modifications he desired to the planned military combinations.

Unable to impose his will on a subordinate protected by his prestige, the First Consul reversed his plan. What he doesn't dare do on the Rhine, I will do on the Alps

, he decided.

Backup plan

The new arrangements stipulated that the Reserve Army would cross the Alps to attack Melas , thus trapping it in a pincer movement between the Army of Italy, positioned around Genoa. The role of the Army of the Rhine was now limited to pinning down Pál Kray's forces in Swabia [Schwaben]. It was to prevent them from coming to Melas's aid in Lombardy.

However, this maneuver could not lead to results as decisive as those initially envisioned. Peace could not result from it. In this instance, Bonaparte was perhaps being too deferential to Moreau, to whom he continued to lavish displays of friendship. He probably did not consider his authority sufficiently established to punish the insubordination of such a popular general. Consequently, the First Consul refused Berthier the firm measures he demanded against the recalcitrant general.

Austrian Offensive on the Riviera

The Austrians launched their offensive in Italy on April 6, 1800. Facing them, Masséna had unfortunately divided his 40,000 men into two corps. The first, positioned between Nice and the Col de Tende [44.14958, 7.56181], guarded the French border; Louis-Gabriel Suchet commanded it. The second, led by Jean-de-Dieu Soult, watched over the approaches to Genoa.

This deployment soon produced disastrous results. The Austrians drove Suchet back to the Var River, Soult to Savona , and Masséna, his army cut in two, was forced to retreat to Genoa and then entrench himself there.

On April 9, the enemy began the siege of the city. Masséna, who had known since receiving a letter from the First Consul a few days earlier that he would receive neither reinforcements, nor supplies, nor equipment, had no choice but to wait for the arrival of the Reserve Army. Until then, he had to hold out, relying on sorties for resupply.

Preliminaries in Germany

But intervention in Italy required Moreau to first begin his operations in Germany. However, he was proving frustratingly slow. It was only on April 24th that he began to cross the Rhine, after a vehement demand from the First Consul. On May 1st, his entire army was finally massed on the right bank of the river.

Stockach fell on May 3, Moesskirch [Meßkirch] on the 5th. Moreau then established himself in Augsburg and Munich [München] , without having given battle to Pál Kray, who was able to retreat to Ulm without even having to cross the Danube for protection. Once in Bavaria [Bayern], Moreau lapsed back into his lethargy.

The essential objective, however, had been achieved. The Army of the Rhine cut off the Austrians' route to Bavaria and Tyrol. Moreau did not believe himself capable of doing more, especially since the Minister of War, Carnot, had ordered him to send Claude Jacques Lecourbe and his 25,000 men to guard the St. Gotthard and Simplon passes. Not without vigorous prior protest, Moreau finally agreed to dispatch 14,000 soldiers toward the Saint Gotthard Pass, under the command of Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey. Then he halted.

The second campaign of Italy, day after day

The second campaign of Italy, day after day

Beginning of the Campaign

Alongside these German operations, the Reserve Army continued to concentrate, officially in Dijon, but in reality in Geneva and on the north shore of Lake Geneva , in the utmost secrecy. Thanks to the skill of Berthier and Carnot, the Austrians remained unaware of this.

Route Selection

Several routes were available for descending into Italy. Those passing through northern Italy were considered first:

- The route from Zurich [Zürich] to Milan [Milano] via the Splügen Pass and Lake Como [Lago di Como] . This was the first route considered by the First Consul;

- The route between the same two cities via the St. Gotthard Pass and the Ticino Valley.

Both required the support of Moreau's right wing. Hence the detachments requested from him.

At the end of March 1800, the possibility of using a route further west began to be discussed. This would allow for a faster advance to Masséna's aid. After some hesitation, this option was finally chosen.

The remaining question was which of the Valais passes to use. On April 27, Bonaparte made his decision. The Great St. Bernard Pass [45.86896, 7.17060] was chosen over the Mont Cenis and Simplon Passes. Although the most difficult of the three to cross, it offered other advantages: a shorter route, a road passable by carriage as far as Bourg-Saint-Pierre , six or seven kilometers from the summit. The most challenging section of the route was then only about twenty kilometers long.

Besides its convenience, strategic reasons also favored this route.

- First, the situation was deteriorating on the Mediterranean coast (to such an extent that on May 11, Nice would fall to the Austrians). Being able to reach it quickly was therefore crucial.

- Second, this route led to a crossroads providing access south to Piedmont [Piemonte] and east to Lombardy. Therefore, the final direction of the attack could be decided at the last moment, depending on the circumstances.

- Furthermore, by advancing with the Reserve Army through the Aosta Valley, the First Consul would find himself at the center of a defensive line that also included the arrival of 4,000 soldiers via Mont Cenis under the command of Louis Marie Turreau , another 5,000 under Joseph Chabran via the Little St. Bernard Pass, Antoine de Bethencourt's division via the Simplon Pass, and the 12,000 men that Moncey was bringing from the Army of the Rhine via the St. Gotthard Pass.

- Finally, even if its offensive failed, the French army, having taken control of this pass, would have a guaranteed line of retreat.

Departure of the First Consul

On May 6, Bonaparte left Paris. Officially, he was heading to Dijon for an inspection. If he does indeed stop there on the 7th, the First Consul immediately continues his journey to Geneva, arriving there on the 9th before dawn.

After giving Jean Lannes command of the vanguard and Joachim Murat command of the cavalry, and especially after studying the route over the Great St. Bernard Pass with General Armand Samuel de Marescot , Inspector of Engineers, he sets off again for Lausanne, where, on the 12th, he reviews the Chambarlhac and Loison divisions on the Saint-Sulpice plain west of the city [46.51021, 6.54634]. [46.51021, 6.54634]

The following day, Napoleon reviews the Boudet division in the Vevey market square. On the 16th he moved to Saint-Maurice-du-Valais , then the next day to Martigny, where he set up his Headquarters [46.10028, 7.07356].

Crossing of the Great St. Bernard Pass by the Reserve Army

The vanguard, specifically, left Martigny two days prior to begin its ascent of the pass . The two thousand meters of elevation gain to the summit (at an altitude of 2,469 meters) required a good eight hours of climbing, at least for the infantrymen.

On this terrain, the horses proved slower than the men. The artillerymen even more so, having to haul hollowed-out tree trunks in which their disassembled guns had been placed (the wheeled carts intended for their use proved unsuitable). The task proved so arduous that the peasants recruited to carry it out left after a few hours of work.

Once the pass was crossed, the French vanguard hastened towards Ivrea. It drove ahead of it a thousand Croats, dislodged from Etroubles , who retreated towards Aosta and then Châtillon. On the 18th, it entered this town.

Resistance of the Bard Fort

But the next day, Lannes and his men encountered the Bard Fort , which overlooked the Dora Baltea valley some fifteen kilometers from its outlet into the Po plain. The strength of its defenses had been underestimated: four hundred soldiers manned twenty-six cannons.

This was enough to block the passage of the French artillery, which, unlike the infantry and cavalry, could not bypass the obstacle via mountain paths, such as the one that passed through Albard and Rovarey, which the First Consul himself would later use.

Meanwhile, the various divisions in turn completed their ascent of the Great St. Bernard Pass. The last corps — the Consular Guard — crossed the pass on May 20, accompanied by Bonaparte. Contrary to the heroic depiction Jacques-Louis David would later give of the episode, the First Consul traveled for the occasion on the back of a mule, an animal with a more sure footing than a horse. On the 21st, he arrived in Aosta.

At that moment, the Bard stronghold was about to collapse. After three days of paralysis, and while the First Consul fumed, Auguste Viesse de Marmont had found the solution. To overcome the obstacle as stealthily as possible, the only road running at the foot of the fortress was strewn with manure, the wheels of the gun carriages were wrapped in straw, and soldiers took the place of horses as draft animals. The batteries then crept under the citadel walls at night. Despite these precautions, Marmont estimated the losses at 5 or 6 men per wagon.

The advance could then resume:

- On May 22, 1800, Lannes' vanguard captured Ivrea.

- On the 26th, a few kilometers south of the city, the battle of the Chiusella Bridge took place [45.412863, 7.88211]. The 6th Light Division, the 22nd and 40th Divisions engaged the cavalry of General Károly József Hadik von Futak in a bayonet charge and routed them.

- On the 28th, the vanguard reached the banks of the Po at Chivasso .

The first part of the campaign proved a resounding success. The Austrians, convinced that Bonaparte would rush to the defense of Nice , were waiting for him near Susa. They saw him appear behind them.

The Campaign Continues and Concludes

Surprise for the Austrians

The Austrian commander-in-chief, Melas, was informed as early as May 21st of the French army's crossing of the Great St. Bernard Pass, but he was convinced it was merely a diversion. He delayed until the 28th before advancing on Cuneo with 10,000 men. There, he realized that the French were indeed threatening his line of retreat and prepared to defend the right bank of the Po River by assembling 30,000 troops around him.

Bonaparte in Milan

- For his part, Bonaparte finally decided to head for Milan. This choice resulted from a number of considerations, some more relevant than others, but which, taken together, fully justified this move:

- On the one hand, Bonaparte, despite Masséna's increasingly alarming messages, did not believe Genoa would fall. He considered the city too difficult to storm for the Austrians to succeed. He underestimated the famine raging within the city walls, threatening to incite the population to revolt against an exhausted French army, which was also running out of ammunition.

- Moreover, the objective assigned to the Army of Italy had already been achieved. By entrenching himself in Genoa, Masséna had tied down the Austrians during the Reserve Army's crossing of the Alps . Furthermore, the battles he had fought around the city and those fought by Suchet's division in the Var region had cost the enemy a third of its forces. In his view, the re-establishment of the Cisalpine Republic, which the First Consul intended to proclaim upon arriving in Milan, would constitute such a threat that Melas would have to take it into account. In grave danger of being cut off from his bases, the Austrian general could only lift the siege of Genoa, regroup his troops, and attempt to force his way into Tyrol [Tirol] and Austria.

- In Milan, Bonaparte knew, having already experienced it in 1796, that he would be welcomed as a liberator.

He finally entered the city on June 2nd.

Austrian Reaction

When he understood the situation, Melas reacted as expected by abandoning the capture of Genoa and recalling the units operating in France. He planned to concentrate them around Alessandria, a city on the Tanaro River with an imposing, modern citadel .

Feldmarschalleutnant Peter Karl Ott von Bátorkéz , who was besieging Genoa, received orders to withdraw on June 2nd, the very day that Masséna resigned himself to entering into negotiations. Consequently, the Austrian general postponed his departure, and the convention (Masséna refused to sign any document containing the word "capitulation") was ratified on the 4th. The heroism of his resistance and the impatience of his adversaries allowed Masséna to negotiate advantageous terms. His men, in particular, were authorized to return to France to resume the fight. They would thus reinforce Suchet, who would soon reoccupy the Alpes-Maritimes and the Riviera, evacuated by the Austrians.

Melas found himself effectively with an army trapped in the Piedmont plain.

Crossing of the Po by the French. Concentration at Stradella.

If he wanted to break out, he would have to push back the Reserve Army, which was rushing towards the Po to take up positions at the various possible crossing points. On June 3rd, General Guillaume Philibert Duhesme entered Lodi , on the Adda River ; on the 4th, Murat reached Piacenza, on the Po; On the 6th, the French, having crossed to the right bank, concentrated at Stradella .

The choice of this position was no accident. At this point, the foothills of the Apennines [gli Appennini] come closest to the river. The road from Alessandria to Piacenza was thus constricted into a narrow corridor, easy to blockade. Positioned there, holding the bridges from Belgioioso to Cremona, the French army blocked the Austrians' most likely line of retreat, while remaining capable of advancing towards Ticino or the Lombard plain should the enemy take another route.

Advance towards Alessandria

News of the fall of Genoa, received on June 8, led Bonaparte to fear that Melas might also take refuge there or attempt to escape northwards through the lake region. He therefore decided to launch an offensive: 24,000 men marched on Voghera , heading towards Alessandria. The First Consul himself left Milan on June 9 to join his troops.

On the same day, Lannes and his vanguard successfully engaged General Ott's corps, which was advancing from Genoa, at Montebello [45.00111, 9.10438] and its surroundings.

Marengo and the end of operations

On June 13, observing the inaction of the Austrians following their defeat at Montebello, Bonaparte advanced. The enemy remained elusive. Some reports suggested they had moved north. These would prove to be false. However, they appeared all the more credible as they unwittingly reflected debates within the Austrian General Staff. Many of its members believed that avoiding combat would offer only advantages. They proposed crossing the Po River at Casale, marching on Ticino, which the French had left undefended, and thus trapping the enemy in a pincer movement between the main body of the Austrian army and the numerous strongholds still held by its garrisons in Piedmont. Fearing that his prey might escape, the First Consul dispatched the divisions of Jean-François de Lapoype and Louis Charles Antoine Desaix in search of it. The former would inspect the area around Valenza to the north; the latter, recently returned from Egypt, those around Novi [Novi Ligure] to the south.

Consequently, when the battle of Marengo began, 31,000 Austrians, equipped with about a hundred artillery pieces, faced 20,000 French, barely equipped with 25 cannons.

The battle initially went in favor of the Austrians, to the point that Melas relinquished command to his lieutenants around five o'clock in the evening. He would soon regret this decision. The return of Desaix's division, drawn by the sound of cannon fire or alerted by Bonaparte, and above all a decisive charge by the dragoons of François Étienne Kellermann (the son of the victor of Valmy), tipped the scales of victory in the French camp. The Austrians retreated to Alessandria via the bridge over the Bormida River, leaving the battlefield to Bonaparte's troops.

Detailed article on the Battle of Marengo

This French victory was, moreover, quite relative, as Melas retained the means to contest it. He nevertheless agreed the very next day to sign an armistice that was highly detrimental to Austrian interests. His army withdrew to the Mincio River and surrendered all the strongholds it still held in northern Italy, including the city of Turin [Torino] .

Consequences

Consular propaganda would lend luster to a militarily lackluster victory. Contrary to his public pronouncements, the First Consul harbored no illusions about the circumstances of the battle or his role in it. Contemporary accounts attest to this. He fully intended, however, to extract every possible benefit from the outcome. Even before the campaign, he wrote to his brother Joseph: A victory will leave me free to do whatever I wish

. Subsequent events would prove him right.

Ultimately, the Second Italian Campaign would represent a political triumph for Napoleon Bonaparte far more than a military one.

Map of the Italian campaign of 1800

Sources

This page is primarily based on the book by Patrice Gueniffey, published by Gallimard in 2013, entitled Bonaparte (1769-1802).Crédit photos

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon and Empire association. Thanks to Mr. Ugo Valfer (photos of the Alessandria citadel) and Mr. Cyril Maillet (aerial photos of the Alps) for their kind contribution.