Anne-Louise-Germaine de Staël

Baroness of Staël-Holstein

Pronunciation:

Germaine de Stael was born in Paris on April 22, 1766, the only daughter of Jacques Necker - a shrewd Genevan banker who became a mediocre minister under Louis XVI - to whom she devoted a lifetime of unbounded admiration. Her high self-esteem, the education she had received and the environment in which she had been brought up - Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, Jean le Rond D'Alembert, Jean-François Marmontel, Edward Gibbon, Abbé Raynal and Jean-François de La Harpe were all familiar faces in her household - encouraged her early on to pursue the arts. As early as 1788, two years after her marriage to Baron Erik Magnus de Staël-Holstein, Swedish ambassador to Paris, she published her Lettres sur les ouvrages et le caractère de Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Like the La Fayette, Benjamin Constant, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, Condorcet and other representatives of new ideas who populated her own salon, Madame de Staël was initially favorable to the Revolution, dreaming of playing a political role in it. But her ideal of constitutional monarchy soon made her suspect, and she was forced into exile in England in 1793.

Returning to Paris after Thermidor, she first published Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine, a plea in favor of Marie-Antoinette. Her essay Des circonstances actuelles qui peuvent terminer la Révolution et des principes qui doivent fonder la république en France failed to find a publisher. She had more success with De l'influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations and De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales, printed in 1796 and 1800, followed by her novel Delphine (1802). This period also saw her separate from her husband (1796) and lose him (1802).

Madame de Stael met Napoleon Bonaparte through Talleyrand, at a reception on January 3, 1798 at the Hôtel de Galliffet . She imagined she could become his muse and make him a liberal to her liking. But Napoleon Bonaparte didn't appreciate this ugly, pretentious woman, who also wanted to give him lessons. Their disagreement soon turned to hatred. Under the Consulate, Germaine de Stael's salon became a haven for opponents of the regime, known as ideologues, whose ardor she never hesitated to inflame. For example, it prompted Benjamin Constant, a member of its coterie and of the Tribunate, to deliver a speech before the assembly announcing the birth of a new tyranny. In October 1803, Madame de Stael was banned from going within forty leagues of Paris. She took refuge in her father's Château de Coppet in Switzerland.

Germaine de Stael found solace from this "exile" in her literary works and in the arms of Benjamin Constant and Albert de Rocca, a young Swiss officer twenty years her junior, with whom she exchanged a promise of marriage in 1811 (kept in 1816). She also received numerous visits from friends and admirers, and traveled throughout Europe. These years saw the publication of her novel Corinne (1807) and, above all, an essay, De l'Allemagne, printed in 1810 and seized by order of the Emperor - the book was finally published in France shortly after Napoleon I's first abdication, and had a considerable influence throughout the 19th century on French perceptions of their neighbors across the Rhine. The latter work was the height of the Emperor's anger towards Madame de Staël. He forbade her to publish and placed her under house arrest at his Coppet estate.

She soon escaped, however, without anyone trying to stop her, and this time set off on a veritable exile, staying successively in Russia, Sweden and England. Everywhere, she worked to unite Europe against Napoleon 1st.

She did not return to France until the spring of 1814, after the fall of the Empire. Having initially seen fit to stay away at the start of the Hundred Days, she tried again to play a political role when the Emperor indirectly solicited her support. To this end, she pushed Benjamin Constant into the arms of Napoleon I, offering him the liberal endorsement he desired.

She died two years later, on July 14, 1817, after several months of agony following a stroke (January 5, 1817).

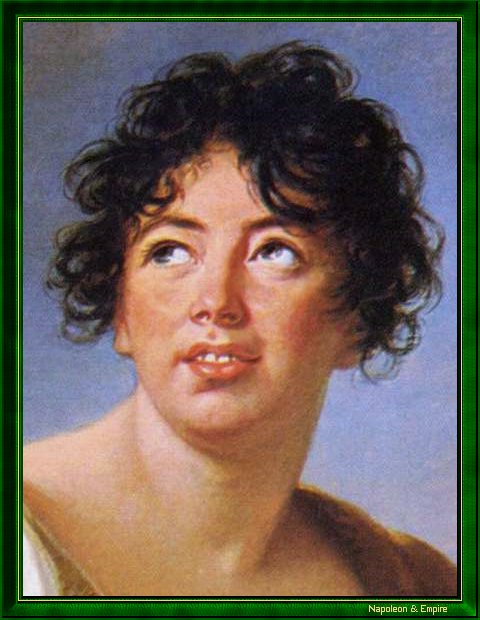

"Anne-Louise-Germaine de Staël" by Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (Paris 1755 - Paris 1842).

In 1818, her children published his Considérations sur les principaux événements de la Révolution française, to which Stendhal responded with his Vie de Napoléon.

Perhaps remembering Bonaparte's answer to his question: General, what do you consider to be the most important woman?

- She gave birth to three sons and two daughters, probably from four different fathers.

Madame de Staël once called Napoleon Robespierre on horseback

. This remark shows how little she understood either of them.

Philately: in 1960, Les Postes de la République Française issued a 0.30 F stamp bearing the effigy of Germaine de Staël.

Other portraits

"Anne-Louise-Germaine de Staël" by François Pascal Simon Gérard (Rome 1770 - Paris 1837).

"Germaine Necker, baroness of Staël-Holstein a.k.a. Madame de Staël" by Marie Eleonore Godefroid (Paris 1778 - Paris 1849) after François Pascal Simon Gérard.

"Madame de Staël" by Wladimir Lukitsch Borowikowski (Myrhorod, Ukraine 1757 - Saint Petersburg 1825).