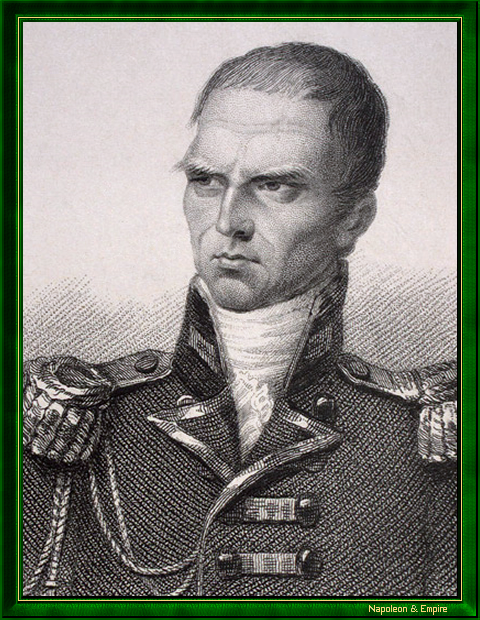

Hudson Lowe

Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Military Order of the Bath

Pronunciation:

Hudson Lowe was born on June 28, 1769 in Galway, Ireland. The son of a surgeon-major, he was raised in the army.

In 1793, while a lieutenant, his regiment was sent to Corsica to support the anti-French insurgents. Lowe was then garrisoned in Minorca, where he organized and commanded a free company made up of Corsican refugees. At its head, he fought the French during their Egyptian expedition. The unit was subsequently disbanded.

When hostilities resumed between France and England after the breakdown of the Peace of Amiens, he was tasked with creating a similar corps, the Corsican Rangers, with whom he occupied the island of Capri in May 1806. Two years later, he surrendered to General Jean Maximilien Lamarque, who had landed on the island with 3,000 men.

Promoted to colonel in 1812 , Lowe was tasked the following year with inspecting the Russo-German Legion formed by Tsar Alexander I from German deserters from the French Invasion of Russia. After meeting Madame de Staël in Sweden, he went to the front and witnessed the battle of Bautzen, during which he saw Napoleon I for the first time .

In October 1813 , Lowe was attached to the headquarters of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. After being a mere observer at the battle of Leipzig (a.k.a. Battle of the Nations) , he went to Holland to oversee the raising of Dutch troops, then rejoined the Prussian army as a representative of the British high command. In this position, he earned the esteem and trust of the old general and his chief of staff, whose views he fully shared: they had to go to Paris and dictate the peace terms to the regime that would replace the destroyed Empire.

After Napoleon's abdication, it was Lowe who brought the news to London. His promotion to the rank of general followed shortly afterwards.

When hostilities resumed in 1815 , he was given command of an expeditionary force tasked with invading southern France. He was occupying Marseille when he was offered the post of governor of the island of Saint Helena, where Napoleon was to be exiled . The offer included promises of promotion and a substantial salary. Lowe accepted.

The instructions given to him in London stipulated that Napoleon should be treated as a prisoner of war and that a guard should be set up around him that was as gentle as possible but strict, prohibiting him any possibility of escape as well as any communication with anyone except through the governor of the island.

Lowe embarked for Saint Helena on January 29, 1816, accompanied by his wife and two stepdaughters. He took with him nearly two thousand volumes intended for his prisoner.

Napoleon initially welcomed the news of his arrival, pleased to be dealing with a military man who had served under Blücher and commanded Corsicans. The first meeting between the two men, on April 14, 1816, went well. But Lowe immediately expressed concern about increasing security around the captive. The second meeting between Napoleon and Lowe, on April 30, gave the former Emperor the opportunity to complain about his treatment by England and his conditions of captivity (the island's inhabitants were forbidden to speak to him). The new governor remained inflexible.

In the days that followed, Lowe displeased Napoleon by extending an invitation to "General Bonaparte" to attend a reception at Plantation House, the governor's residence. A few days later, on May 16 or 17, during their third meeting, Napoleon bitterly complained about this and bluntly accused Hudson Lowe of having been sent to assassinate him. The rift between the two men was established and would persist.

The fourth interview took place on June 19 (according to Emmanuel de Las Cases) or June 20, in the presence of a third party, and went well.

The fifth meeting, on July 17th, a private encounter, gave Napoleon the opportunity to voice his grievances for two long hours: the boundaries within which he could move about without being accompanied by a British officer were too narrow; he could not communicate with anyone on the island without going through the governor; he could not send letters without them being opened; his entourage was subject to the same rules as him; and his stay at Longwood was unhealthy. Finally, he reproached Lowe for his meticulous adherence to instructions, unworthy of a general officer, and for his bad faith.

A new meeting took place on August 18th, the last and most stormy. It occurred against a backdrop of massive cuts in British spending on Napoleon's upkeep. He was even invited to cover the additional costs by turning, if necessary, to his stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais. Napoleon, arguing that he was unable to communicate freely with his friends, refused. The already strained relations between Lowe and Count Henri Gatien Bertrand, who served as the Emperor's intermediary, worsened on this occasion and culminated in a complete break. The meeting between Napoleon and Lowe took place two days after this incident, in the presence of Admiral Pulteney Malcolm. After feigning ignorance of the governor, Napoleon, when directly addressed by him, sided entirely with Bertrand, called Lowe a butcher, and informed him that he no longer wished to have any dealings with him.

This wish was granted. The governor of Saint Helena did not see his prisoner again until five years later, after Napoleon's death.

Lowe left Saint Helena on July 25, 1821 to return to England. There he faced public hostility following the pamphlet published by Dr. O'Meara, defended himself poorly, and finally accepted the position of Deputy Governor of Ceylon, where he went in 1825.

In 1830, the opposition, made up of men who had previously supported an agreement with Napoleon, came to power and forced him to leave his post.

"Sir Hudson Lowe". Print of the nineteenth century.

Sir Hudson Lowe was probably not the torturer and executioner that Napoleonic legend has made him out to be. But the positions he held condemned him from the outset. An angel from heaven could not have pleased us, had he been governor of Saint Helena

, said the Count of Montholon. And Las Cases wrote: We were left with only moral weapons; we had to systematize our attitude, our words, our feelings...

. Lowe's role was thus predetermined, whatever his personality may have been, in the final battle Napoleon waged to establish his legend. One might, however, think that Lowe's anxious, suspicious, and meticulous nature made the Emperor's task easier.

The Duke of Wellington was not the last to speak in very harsh terms of the jailer of Saint Helena: (He was a) very bad choice; he was a man wanting in education and judgment. He was a stupid man, he knew nothing at all of the world, and like all men who knew nothing of the world, he was suspicious and jealous.