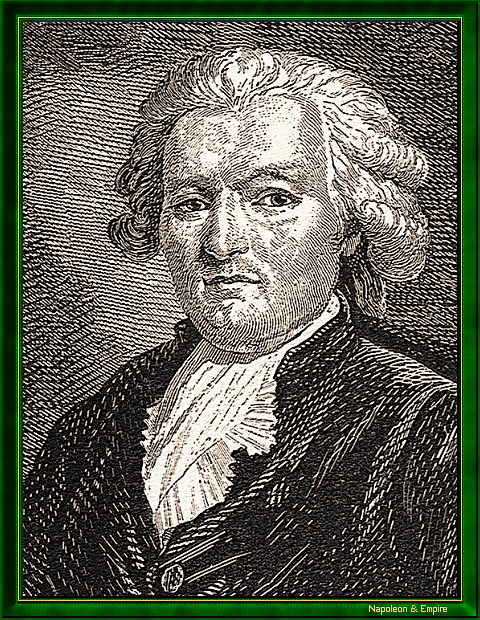

Jean-Anthelme Brillat de Savarin

Knight of the Empire

Pronunciation:

Jean-Anthelme Brillat was born in Belley , Bugey, on April 2, 1755. Heir to a line of magistrates, the young man studied and practiced law in his native town.

Elected as a deputy for the Tiers Etat at the Assemblée Constituante, he made a name for himself with a speech against the abolition of the death penalty. But as a royalist and Girondin, accused of "moderantism", he was forced into exile in Switzerland, then Holland, from where he embarked for the United States.

In this young America, he lives off French lessons and a job as a violinist in the orchestra of New York's John Street Theater. It was also an opportunity to discover turkey, welsh rarebit and korn beef (semi-salted beef), and to teach the art of scrambled eggs to a French chef, Jean Baptiste Payplat, former cook to the Archbishop of Bordeaux, who had settled in Boston where he owned a restaurant. He thus revived the memory of his mother, a remarkable cordon bleu chef.

Back in France in 1796-1797, after being stripped of all his possessions, he was appointed secretary to Charles Pierre François Augereau in the Army of the Rhine, a position he held until his death.

Jean-Anthelme Brillat was a bachelor with little temptation in petticoat pleasures but his interests were eclectic: he was fond of archaeology, astronomy, chemistry, hunting and music, and in 1819 published an Essai historique et critique sur le duel, and a Mémoire sur l'archéologie de la partie orientale du département de l'Ain (Bugey). Nevertheless, his great passion remained gastronomy.

Enjoying fine dining and entertaining frequently at his Parisian home, he took to the stove to concoct a few specialties, such as tuna omelette or filet de boeuf aux truffes.

In the meantime, one of his aunts bequeathed her fortune to him on condition that he add the patronymic of her donor to his own: Savarin.

While Europe was shaken by political storms, battles and the echo of cannon fire, Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was dreaming, meditating and peacefully writing the book that would make him famous: The Physiology of Taste, a code of gastronomy and treatise on culinary science as much as a testimony to the mores of the Empire's rather gourmet society. This epicurean and hedonist legislator thus became the poet of gourmandise.

The book was an immediate success. It aroused the enthusiasm of the young Honoré de Balzac, who wrote No author had given the French phrase such vigorous relief since the 16th century. While some elevated him to the pinnacle of gastronomic philosophy, Marie-Antoine Carême was jealous. Later, Charles Baudelaire scorned him. It's true that, as Brillat-Savarin wanted to turn the art of cooking into a veritable science, his explanations are tainted with a certain pedantry, which is offset by a generally elegant style, numerous anecdotes and touches of humor.

The dear man hardly enjoyed his fame. On January 21, 1826, shortly after the publication of his work, he caught a cold at an anniversary mass in memory of the death of Louis XVI in the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Pleurisy took him to his grave eleven days later.

Gastronomes, taphophiles and other history buffs can visit his tomb in the 28th division of the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris .

"Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin". Nineteenth Century engraving.

To invite someone over is to take charge of their happiness for the entire time they are under your roof. This is how Brillat-Savarin popularized the word "conviviality," which took on its full meaning.

Today, if the general public may have forgotten the reason for Brillat-Savarin's fame, they at least know his name thanks to a cheese created in 1890 and renamed in his honor in the 1930s by Henri Androuët.