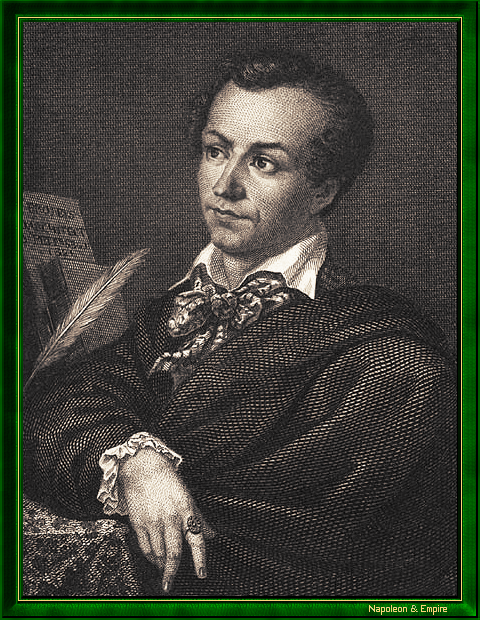

Marie-Antoine Carême

Pronunciation:

In 1792, as the Revolution in Paris starved even more, Marie-Antoine (known as Antonin), born in the capital on June 8, 1784, poor among the poor, left his family to try his luck. Of his many children, his father felt that only this one could possibly rise socially. Intelligent, cunning, endowed with great curiosity and a boundless thirst for learning, the little fellow was to succeed far beyond his father's expectations.

His first good luck came with an apprenticeship with a tavern owner, who taught him all the rudiments of cooking.

His second chance came five years later, when he was hired by Sylvain Bailly, the caterer to the great fortunes of the day, who, in addition to the teenager's culinary talents, noticed his gift for architectural design in the construction of dishes. Bailly introduced him to the Bibliothèque de la Nation, where he studied all the architectural drawings (pagodas, palaces, Turkish pavilions, rotundas, fountains) that provided inspiration for his table settings and table decorations...

After the hell of the back kitchen came the paradise of glory. Carême was one of those chosen few who possess the intelligence of the material and know how to speak to the ingredients.

In the service of the greatest, he also became their friend. Among them was Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, who employed him both in Paris and in Valençay , and sincerely admired him as one of his peers.

Antonin, a star chef, brought luxury to the table of the tsar Alexander I, the King George III of England, the Emperor Francis I of Austria and many others before settling in Paris.

During the Restoration, King Louis XVIII forgave him his service to the Empire and authorized him to call himself Carême de Paris. Always jealous of his independence, Antonin continued to innovate with absolute genius and unparalleled sensuality. He was one of the first chefs to achieve international renown.

An advocate of pleasure without guilt, he believed that two good meals are better than four mediocre ones, and while he opted for simplicity of result, he refused to be modest with his ingredients. However, while he believed that cooking should be decorative, he also professed that it should be in keeping with hygiene, and was capable of establishing dietary regimes.

His health having been exhausted by thirty years of ceaseless effort, he fell seriously ill and had to go to bed, concerned at the idea of leaving unfinished work that he considered essential to his art. He spent his last moments dictating notes to his daughter, and died at the age of forty-eight, on January 12, 1833. His premature death was thought to have been caused by the large quantities of toxic charcoal fumes he inhaled throughout his life.

His tomb , in the Parisian cemetery of Montmartre, remains very well maintained to this day.

"Marie-Antoine Carême". Nineteenth Century engraving.

Carême is credited with the creation of the toque in 1821, which replaced the cook's cotton bonnet, during his stay in Vienna in the service of Lord Charles Stewart.

In addition to developing new sauces, he published a classification of sauces into four basic groups: German, béchamel, Spanish and velouté. He is also credited with replacing the complicated French-style service (presentation of all dishes at the same time) with the easier, less expensive Russian-style service, in which the dishes are presented as they are served, with the meat or poultry already cut up. Service à la Russe, which had already begun in 1810, developed further after Carême's death. Nevertheless, one tradition of show cooking endured in French homes: the cutting up of poultry at the table by the host...