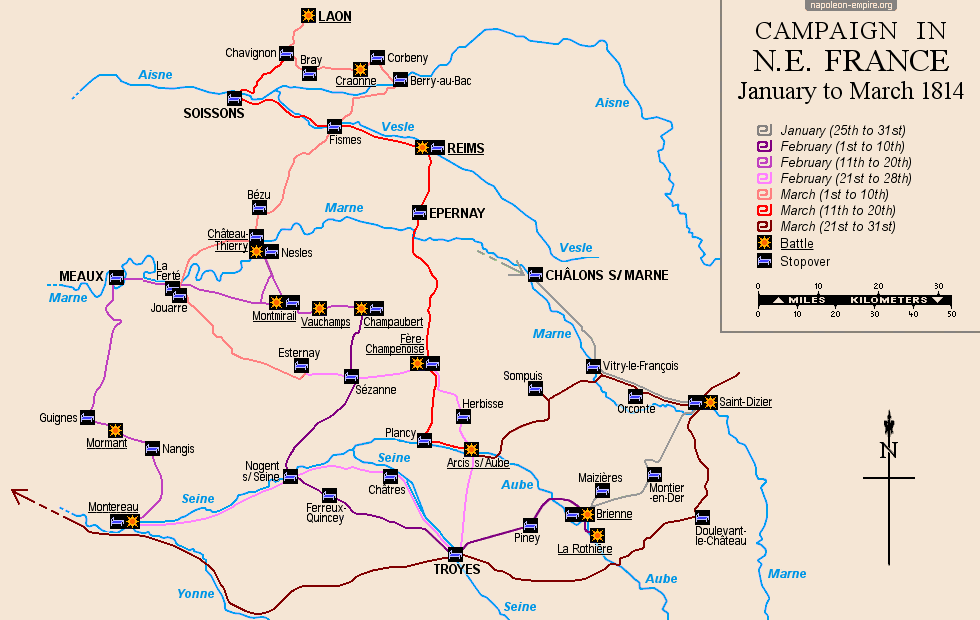

Military operations of the campaign of 1814 in Northeast France

In January 1814, Napoleon I put on his Italian campaign boots

and set off to stem the Allied tide in northeastern France. He succeeded for two months, relying on inexperienced troops - the famous "Marie-Louise" - ill-equipped and far too few in number. At the cost of an outpouring of energy and daring, jumping from one field of operations to another, he succeeded in creating a moment of doubt in the enemy command.

But the facts were stubborn: too great a disparity of forces, the weariness of his army chiefs, the pusillanimity of the men to whom he had entrusted the keys to his capital, betrayal at last, would finally get the better of this last surge.

Napoleon's last military masterpiece, under which Bonaparte was now emerging, the French campaign is no less beautiful for having ended in defeat.

State of forces at the start of the French campaign

At the beginning of January 1814, Napoleon had around 150,000 soldiers at his disposal. To the 60,000 to 70,000 he had brought with him from Germany at the end of November 1813, he had added 150,000 reinforcements. But this theoretical strength of 220,000 was soon reduced by a third as a result of typhus epidemics in December 1813.

These forces were distributed as follows:

- 36,000 men in the Netherlands, 20,000 of whom occupied strongholds, the rest commanded by General Nicolas-Joseph Maison;

- 22,000 on the Lower Rhine, under Marshal Etienne Macdonald;

- 10,000 in Lorraine, under Marshal Michel Ney;

- 20,000 on the Middle Rhine, under Marshal Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont;

- 14,000 on the upper Rhine, under Marshal Claude-Victor Perrin, known as Victor;

- 36,000 in strongholds on the Rhine and Swiss border;

- 12,000 on the Swiss border, under Marshal Édouard Mortier;

- 1,600 in Lyon, under Marshal Charles Augereau.

The field corps (Marshals Macdonald, Ney, Marmont, Victor, Mortier) therefore comprised a total of just 78,000 men. As for the 10,000 to 20,000 men in reserve in Paris, they would only step in when the Marshals' numbers had already melted away.

On the Allied side, the Generalissimo, Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg, had his own army of 200,000 men, made up of Austrian and German troops and a Russian corps under Peter zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. He also had under his command, at least nominally, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, who commanded 65,000 Prussians. Other corps arrived later: those of Ferdinand von Wintzingerode, Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf, Duke Ernest of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Crown Prince Louis of Hesse...

Without even taking into account the forces invading Holland under Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (in his capacity as Crown Prince of Sweden), there were 265,000 Allies marching against 115,000 French (if we exclude the 36,000 men left in the Netherlands).

Start of operations

Schwarzenberg crossed the border in early January. The various components of his army penetrated France from Strasbourg to the latitude of Neuchâtel (the town had been French since 1806), and the divergent routes he assigned them further stretched a front that extended 450 kilometers from Strasbourg to Dijon. Testifying to this dangerous dispersal, the main corps marching with the general-in-chief numbered barely 30,000 men when it reached Vesoul. Luckily for the Austrian general, neither Victor nor Mortier were in a position to make a move.

As for Blücher, he crossed the Rhine around Koblenz on January 1, then drove Marmont back to the Moselle valley and below Metz. There, he left Johann David Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg, and marched with 28,000 men to Nancy and the Aube .

In mid-January, Schwarzenberg regrouped his forces. He decided to leave only small detachments in front of the strongholds, withdrew several corps to his center, and marched with him towards Bar-sur-Aube , where he was to join forces with Blücher.

The French marshals were unable to put up a fight, and were retreating everywhere. Mortier, who had first advanced towards Chaumont , returned to the Aube valley; Macdonald, who saw Winzingerode cross the Rhine some ten days behind the rest of the invaders, headed for Châlons-sur-Marne (Châlons-en-Champagne); Victor and Marmont withdrew first behind the Meuse and then to the Marne, where they joined Ney on the 24th.

Meanwhile, the main Allied army continued to concentrate. On the 24th, Schwarzenberg was in front of Bar-sur-Aube , where Mortier accepted the battle before withdrawing to Troyes . In the days that followed, the various enemy corps regrouped, with the exception of Yorck. By this time, the Allies had gathered 130,000 men to hold the campaign, the rest having been left behind.

On the 26th, Victor, Marmont and Ney joined forces with Napoleon at Vitry . The Emperor, having brought with him 10 to 15,000 soldiers, had a mass of 45,000 men. He left Vitry with a rearguard (the town was immediately taken by Yorck's troops) and advanced as far as Saint-Dizier, believing he would meet the Allies near Langres. On learning that Blücher intended to cross the Aube, he headed for it. The Emperor's strategy was to prevent Blücher from joining forces with Schwarzenberg.

On January 29, 1814, the Battle of Brienne took place, during which Napoleon hoped to crush Blücher, who, driven by his usual ardor, had already dangerously distanced himself from the Austrian troops as he began his march towards Paris. Although victorious for the French, the battle did not have the desired outcome.

Three days later, on February 1, Blücher attacked in his turn, at La Rothière . Napoleon did not want this battle, otherwise he would probably have struck the day before, when Blücher was reduced to his own forces (25,000 men), or the day before, after Marmont's arrival. As it was, the Prussians, reinforced by the corps of the Royal Prince of Württemberg, Carl Philipp von Wrede and Ignácz Gyulay, lined up some 74,000 combatants against 40,000 French. The French were defeated, losing 2,500 men and 53 cannons . Napoleon sent Marmont to withdraw to Ramerupt, on the right bank of the Aube. For his part, he crossed Lesmont and withdrew to Troyes, where he crossed the Seine to join Mortier.

Instead of pursuing the defeated enemy, Blücher decided to separate himself from the main army and head for the Marne. There, he hoped to find the corps of Kleist, Alexandre-Louis Andrault de Langeron and Yorck. The 50,000 men thus assembled should, in his mind, enable him to push Macdonald's troops, who had just arrived in the Marne valley, back as far as Paris. Schwarzenberg, for his part, had to keep in touch with Napoleon and limit his movements. He followed him to Troyes. The city was occupied by the Allies on February 8: an advance of just 45 kilometers in eight days, and behind a beaten army!

Fighting on the Marne

Napoleon, faced with Schwarzenberg's lack of initiative and pusillanimity, left Victor and Nicolas Oudinot alone with 20,000 men to face the Austrian general and his 100,000 soldiers. On the evening of February 6, having set up his headquarters at the Château de Ferreux-Quincey, the Emperor conceived the maneuver against Blücher that would lead to victory at Montmirail. He was thus able to rush towards the Marne in the footsteps of the Prussian general, by far the most enterprising of his enemies, with forces almost equivalent to those of his adversary. He began his march on February 7 with Mortier and Ney, joining Marmont at Nogent and marching on Sézanne on the 9th.

By this date, Yorck, having driven the French out of Vitry, had forced Macdonald to evacuate Châlons (February 5) and retreat to Epernay , where he followed. On the 9th, he was at Dormans, with his vanguard at Château-Thierry; Blücher was at Vertus and his cavalry had even advanced as far as Meaux , supported by general Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken, with the intention of cutting off Macdonald's retreat; He was joined the same day by Kleist and Pjotr Michailowitsch Kapzewitsch, who had come from Châlons-sur-Marne; Olsufiev was at Champaubert , where the road from Sézanne joins the road from Paris to Châlons; Sacken was at Montmirail with his vanguard at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre. By simultaneously pursuing two opposing objectives: destroying Macdonald's corps and awaiting the arrival of Kleist and Kapzewitch, Blücher had spread his army too thinly, preventing them from supporting each other in the event of an attack. Napoleon, of course, noticed this. He vigorously exploited this error.

On February 10, 1814, Napoleon marched on Champaubert , where he annihilated Zakahr Dmitrievich Olsufiev's corps. Blücher arrived at La Fère Champenoise with Kleist and Kapzewitch's corps, then, on hearing of Olsufiev's defeat, led them back to Vertus.

On the 11th, Napoleon left Marmont behind to conceal his own movement, and marched with 30,000 men towards Osten-Sacken, who, having been sent towards La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, had been ordered to retrace his steps and arrived at Montmirail. Osten-Sacken and his 15,000 men were crushed. Yorck, who was in Viffort , rushed to his aid. The two generals regrouped their forces in the village.

On February 12, pursued by the Emperor, Yorck and Osten-Sacken retreated as far as Château-Thierry . Yorck had to fight a rearguard action that turned into a disaster. Napoleon recaptured the town, while his opponents continued their march towards Oulchy.

On the same day, Kleist and Kapzewitsch were at Bergères-les-Vertus , facing Marmont at Etoges . Macdonald, who had managed to reorganize his troops at Meaux, where they had arrived in disarray, received orders to march on Troyes. On the 14th, he joined Victor and Oudinot at Guignes .

On the 13th, Blücher, informed of the defeats of his lieutenants, who had been pushed back behind the Marne, resumed the offensive. Seeing that Marmont was inert against him, he deduced that Napoleon was marching on Sézanne to reach the Seine valley. He then advanced on Champaubert, hoping to make up for his setbacks in new battles. Marmont was driven back to Montmirail. But Napoleon, having instructed Mortier to pursue Osten-Sacken and Yorck, remained at Château-Thierry.

Realizing that Blücher's offensive offered him the opportunity of a new success, Napoleon joined Marmont at Montmirail on February 14th, arrived at Vauchamps and attacked the overly spirited Prussian general. The latter, with 20,000 men but no cavalry, was driven back to Champaubert with heavy losses.

Between February 8 and 14, Blücher lost 15,000 men and a considerable number of cannons. These days were a disaster for the Allies, and a great success for Napoleon. Satisfied, he crossed the Seine again, taking Marshal Ney with him. Marmont and Mortier remained to face Blücher.

Operations on the Seine and Schwarzenberg's retreat to the Aube

While these operations were taking place on the Marne, Schwarzenberg, instead of gathering his forces to move on Paris, as the victory at La Rothière should have prompted him to do, sent the Royal Prince of Württemberg to take Sens , had Wrede and Wittgenstein attack Nogent, and himself advanced slowly along the lower Seine, multiplying useless movements. Victor and Oudinot retreated behind the river. On February 10, 11 and 12, Victor's troops at Nogent held out admirably against those of Wittgenstein and Wrede. Wittgenstein finally crossed the Seine at Pont-sur-Seine, while Wrede crossed it at Bray, then engaged in battle near Saint-Sauveur with Oudinot the following day. The French marshals had to retreat through Provins and Nangis behind the Yères. Macdonald joined them there with 12,000 men and some troops from Spain. Together, they were now strong enough to hold the position. On the 16th, Napoleon joined them, followed on the 17th by his soldiers, who had performed miracles of speed.

Schwarzenberg set up an excessively extensive system. His troops formed a triangle whose vertices were at Nogent, Montereau and Sens. Three corps were wasted guarding the road between Montereau and Sens, which was not threatened by French detachments of insignificant strength. His reserve was at Nogent, with Mikhaïl Bogdanovitch Barclay de Tolly.

On the 17th, Napoleon attacked Wittgenstein, who returned to Provins after having recklessly advanced much further than expected. The Austrian vanguard at Mormant was decimated. Wrede, even more reckless, suffered the same fate at Villeneuve-le-Comte-Champagne (Villeneuve-les-Bordes ).

On February 18, 1814, in front of Montereau , it was the Prince of Wurtemberg's turn to see his corps assaulted and half-destroyed.

In response to these setbacks, Schwarzenberg retreated to Troyes and recalled Blücher, who had assembled his army at Châlons-sur-Marne. General Winzingerode's corps, which had finally completed its slow ascent of the Meuse, was waiting for Reims . Blücher entrusted him with the task of observing Mortier, while he himself closed in on Schwarzenberg. Marmont followed on his right, stopping at Sézanne.

By the 22nd, Schwarzenberg had concentrated his army around Troyes, on both banks of the Seine, and Blücher had reached Méry . Napoleon, for his part, moved towards Nogent-sur-Seine.

Schwarzenberg was thinking of waging a decisive battle. His forces numbered 150,000, while the French had only 50-60,000. But he learned that Augereau, to the south, had driven General Ferdinand von Bubna und Littitz back into Switzerland. Ever pusillanimous, he suddenly saw in the old marshal and his 20,000 men a grave danger to his campaign in the Paris basin. He therefore sent the Prince of Hesse-Homburg and his 12,000 men to the Rhone, to which he added 30,000 soldiers detached from Austrian troops. These 40,000 to 50,000 men ensured success in this other theater of operations, and in March Augereau was pushed back as far as Valence (Drôme). On the other hand, this drain on the main army, combined with recent setbacks, weakened it to such an extent that the main Allied leaders decided to retreat to Langres and propose an armistice to Napoleon.

Blücher alone disagreed. He felt that such a retreat could only be a prelude to a complete retreat. So he split up again. His decision sealed the fate of the campaign. And his reasons were excellent: Winzingerode was close to joining him with 25,000 men; Friedrich Wilhelm von Bülow was in Laon with 16,000 others from the Netherlands; new troops had left Erfurt and Mainz to join him. In all, 100,000 men will soon be gathered at the Marne under his command, enough to stand up to the French army alone.

Schwarzenberg began retreating on the 23rd. He reached Troyes on the 24th and headed for the Aube. Once Blücher's intentions had been integrated, the allied plan was for the main army to withdraw to Langres, where it would remain on the defensive, while the Prussian general and Prince Louis-Guillaume of Hesse-Homburg took the offensive. Blücher had to rely on the Netherlands, where the corps of Duke Charles-Auguste of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and Bernadotte were stationed in support. All in all, it was essentially a covert retreat.

Napoleon gave Oudinot and Macdonald 25,000 men and instructed them to follow Schwarzenberg. On his own account, with Victor and Ney's corps, he pursued Blücher, who left Méry on the 24th.

Schwarzenberg withdrew his wings from Troyes to Bar-sur-Aube and from Bar-sur-Seine to La Ferté-sur-Aube. On the 26th, Blücher informed the Allied command that the main army was only being pursued by two marshals. The King of Prussia succeeded in persuading Schwarzenberg to halt the retreat and turn against them. Oudinot was attacked on the 27th by the right wing after crossing the Aube at Bar-sur-Aube, and Macdonald on the 28th by the left wing at La Ferté-sur-Aube. Beaten, they were both driven back to the Seine.

Blücher's offensive and withdrawal to Laon

Left to his own devices, Blücher's plan was simple, even simplistic: gather his troops as close to Paris as possible and seize every opportunity.

To join Bülow and Winzingerode, who were occupying the Reims and Laon region, he decided to march on La Ferté-sous-Jouarre via Sézanne. As Marmont was still in Sézanne and Mortier in Château-Thierry, he had to beat the former if he found him in his path, and face the latter. He also had to cross the Aube before Napoleon was on his heels. He succeeded by building a bridge of boats at Baudement, near Anglure.

Seeing this, Marmont left Sézanne for La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, where Mortier joined him on the 26th. Together, they withdrew to Meaux on the 27th. On the same day, Blücher crossed the Marne at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre. He left Yorck behind and sent Osten-Sacken and Langeron to Trilport, a stone's throw from Meaux. On the 28th, Kleist crossed the Ourcq at Lizy-sur-Ourcq to reach the road from Meaux to Soissons , which Blücher was determined to seize. But he was attacked by Marmont and Mortier near Gué-à-Tresmes and, with no support, had to retreat along the road he was supposed to take. Blücher, who had recalled Sacken and Langeron, had no choice but to head upstream along the Ourcq. On March 1, he was not far from Crouy when Napoleon arrived on the Marne.

Abandoning the idea of crossing the Ourcq, Blücher took the road to Soissons via Oulchy the following day, ordering Bülow to close in on him. As a result, Bülow marched on Soissons, finding Winzingerode under the city walls on March 2, and receiving the surrender of his defenders on March 3. This unexpected surrender (resistance had been much longer during the first assault on the town in mid-February) greatly facilitated Blücher's operations. Crossing the Aisne became an easy operation for him, and the concentration of his corps was considerably accelerated. Otherwise, he would have had to bridge the river with boats, or use the undestroyed Missy bridge. The fall of Soissons was therefore probably not the divine surprise that restored him to a hopeless situation, despite what some believe. All the more so as Napoleon, who crossed the Marne at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre on March 3, was two days behind the Prussians.

The Emperor was now looking for a battle, but first wanted to receive some reinforcements arriving in Reims from the Ardennes. Rather than march directly on Soissons, he crossed Château-Thierry, Fismes , from where he sent a detachment to recapture Reims, and Berry-au-Bac , where he crossed the Aisne .

Blücher and his army were still under Soissons. The Prussian general initially planned to attack Napoleon as he crossed the Aisne. He then planned to attack him from the flank between the Aisne and the Lette . On March 6, he advanced on Braye-en-Laonnois , but finally decided not to accept the decisive battle until near Laon, when he learned on the same day that the French had crossed the Berry-au-Bac defile and sent a detachment to Laon .

However, when Blücher withdrew to Laon, he left Winzingerode's infantry on the Craonne plateau , under the command of General Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov (Woronzoff). The position was exceptionally strong. It was impossible for the French to leave it behind. Winzingerode, with 10,000 cavalry, left Braye on the night of March 7-8, 1814 to join the road from Laon to Reims via Fetieux. His mission was to assault the flank and rear of Napoleon, who had to contend with Voronsoff. Kleist and Langeron followed Winzingerode closely; Bülow and Yorck headed for Laon; Osten-Sacken remained at Braye to support Voronsoff.

Napoleon called Marmont and Mortier to Berry-au-Bac, then attacked the Craonne plateau on March 7. Winzingerode, having lost his way on the march, was unable to take part in a battle whose outcome would probably have been different had he been involved. The victory cost Napoleon 8,000 men, which was a considerable loss, especially considering the strength of his forces. Voronsoff lost 4,700 men, but not a single cannon. He was then able to retreat in good order and cover the march of Blücher's army towards Laon. Although lost, this battle was a strategic success for the Allies .

The Battle of Laon took place on March 9 and 10. The French were defeated. In the absence of pursuit, they held out for the next few days on the outskirts of Soissons and Fismes. On March 12, Reims was retaken by the Allies under the command of general Guillaume Emmanuel Guignard de Saint-Priest. Napoleon reacted immediately.

He left the guard of Soissons to Mortier, marched immediately on Reims, fell on Saint-Priest on the afternoon of the 13th, inflicted colossal losses and moved into the city. He spent the 14th, 15th and 16th receiving reinforcements from the Ardennes (4,000 men) and Paris (6,000). On the 17th, he set off again for the Aube, reaching Plancy-l'Abbaye on the Aube , via Epernay and Fère-Champenoise. During this time, Blücher maintained a strict defensive posture, extending as far as Compiègne to secure supplies. He awaited Napoleon's departure, soon made necessary by the superiority of Schwarzenberg's army over those of the marshals assigned to guard it.

Napoleon's return to the Aube

The marshals had to withdraw behind the Seine after further unfortunate engagements, on March 2 at Bar-sur-Seine for Macdonald, and on March 3 on the Barse (a tributary of the Seine) for Oudinot. On the 4th, they had to evacuate Troyes and set up a new defensive line stretching from Nogent-sur-Seine to Montereau. Behind them, Schwarzenberg moved from Sens to the vicinity of Pont-sur-Seine, while Barclay advanced as far as Chaumont. But no sooner had this movement been completed than he received news of Napoleon's probable return to the Aube. Schwarzenberg called Barclay close to him and redeployed his army between the Aube and the Seine.

On the 16th, Wrede and Wittgenstein were ordered to attack Oudinot and Macdonald. The French were driven back to Nangis. On the 18th, Schwarzenberg, knowing that Napoleon had passed Sézanne, thought of concentrating at Bar-sur-Aube . But the French army had already crossed the Aube at Plancy, and Napoleon was at Méry with his vanguard. With the main army's left flank no longer in any danger, Schwarzenberg was, for once, bold enough to attack in his turn.

On March 18, the various Allied corps occupied the following positions: the Prince Royal of Württemberg and Generals Wittgenstein and Giulay were at Troyes, Wrede between Pougy and Arcis, and Barclay at Brienne . Schwarzenberg headed for Arcis , arriving on the 20th as French troops formed up in front of the town. The Allies number at least 80,000; the French less than 30,000. Oudinot and Macdonald were expected to arrive on the evening of the 20th for the Duke of Reggio, and on the 21st for the Duke of Taranto. On the second day of the battle of Arcis-sur-Aube, March 21, Napoleon realized that the enemy's immense numerical superiority, as at Laon, would give them victory.

Last maneuver

He reacted with lightning speed. Breaking off from the battle, he crossed the Aube and reached Vitry on March 21st. Unable to take the town, which was too strongly fortified by the Allies, he moved on to Saint-Dizier. His plan was now to cut off the Allies' main line of communication through Langres and Chaumont, while stunning and frightening the enemy with this unpredictable reaction.

It was not until the 23rd that Schwarzenberg became certain of Napoleon's departure. With a day's march behind him, he decided to stay back, wait for Blücher and then advise him. For the time being, he was content to march on Vitry, arriving the same day.

As for Blücher, he was back in action on March 19, as soon as he heard that Napoleon had left. He sent Kleist and Yorck to Château-Thierry, where Mortier and Marmont had gathered. For his part, with Winzingerode, Osten-Sacken and Langeron, he marched on Châlons via Fismes and Reims, arriving there on the 23rd as well.

The junction of the two armies was complete. The next day, at the instigation of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, the following plan was adopted: march on Paris, Schwarzenberg via Sézanne and la Ferté-Gaucher, Blücher via Montmirail and la Ferté-sous-Jouarre; to conceal this movement, Winzingerode left for Saint-Dizier with 8,000 horses and a few infantrymen.

On the 24th, Napoleon was between Saint-Dizier and Joinville. On the same day, Marmont and Mortier left Château-Thierry and marched to Vitry to join him. Other detachments, at Sézanne, Coulommiers, Meaux and Nogent, were all ordered to join the main French army. But at Soudé-Sainte-Croix, the two marshals found their route blocked by enemy contingents. They could no longer rally the Emperor.

Fall of Paris

The Allied army set off on March 25. Winzingerode took Saint-Dizier as planned. Schwarzenberg attacked Marmont and Mortier, who were defeated in a series of battles and pursued beyond Fère-Champenoise to Sézanne. Near Bergères-les-Vertus , Blücher's cavalry encountered the Pacthod and Amey divisions, which, separated by unforeseen circumstances from Macdonald's corps, were accompanying a large convoy of artillery destined for Marmont and Mortier towards Fère-Champenoise. The Prussians harassed the column along the way, snatching away many guns and carriages, until, on reaching their destination, the two divisions came upon Schwarzenberg's cavalry. All they had to do was lay down their arms and surrender their remaining 60 cannons.

The next day, Schwarzenberg sent Yorck and Kleist from Montmirail to La Ferté-Gaucher to cut off Marmont and Mortier's retreat. But the French escaped via the Provins road and marched towards Paris.

Schwarzenberg and Blücher crossed the Marne on the 28th, arrived in Paris on the 29th at the same time as Marmont and Mortier, fought them on the 30th and entered the capital on the 31st.

On March 26, Napoleon turned against Winzingerode, severely defeating him at Saint-Dizier and driving him back to Bar-le-Duc. It was then that he learned that his maneuver had backfired and that the allies were heading for Paris. His first idea was to follow them back along the Châlons road. A second failure at Vitry and the news of his lieutenants' defeat caused him to change his plans. He returned to Saint-Dizier on the 28th, only to leave on the 29th and attempt to reach Paris via Brienne, Troyes and Fontainebleau. He knew that this route would not bring his troops under the capital's walls before April 2. And, in fact, it would be too late. On the 30th, during the decisive battle, his army was still at Villeneuve-l'Archevêque, between Troyes and Sens, almost 200 kilometers from Paris.

The campaign in Northeast France was over.

In south-west France, Jean-de-Dieu Soult tried to contain Arthur Wellesley de Wellington's offensive until April 12, 1814, when he received the news of Napoleon's abdication.

Map of the 1814 French campaign