Battle of Craonne

Date and place

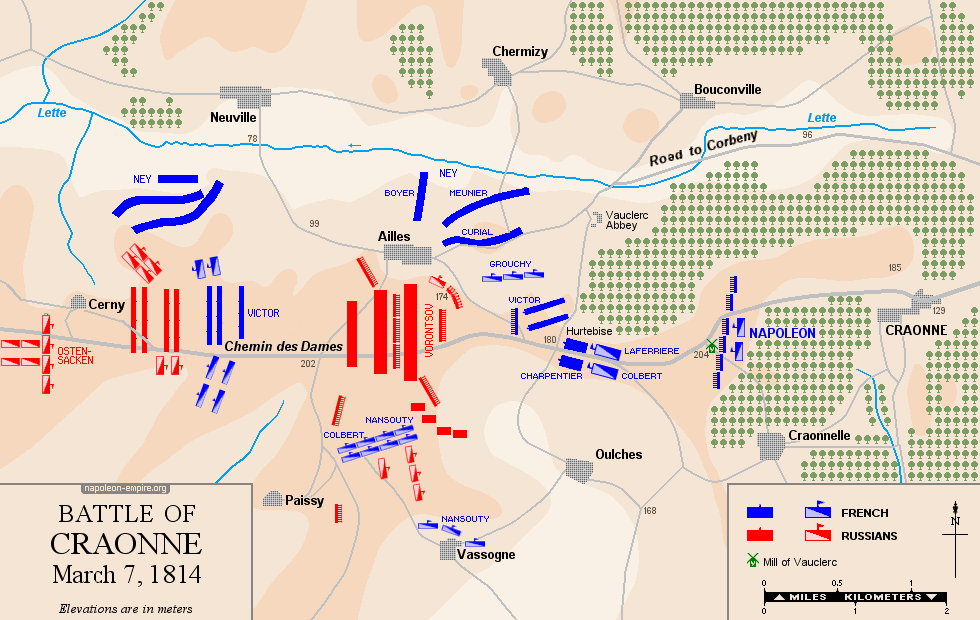

- March 7th, 1814 at Craonne, Aisne, Picardy, northern France.

Involved forces

- French army (37,000 men) under Emperor Napoleon I.

- Prussian and Russian army (90,000 men), under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 5,400 men killed or injured, including Marshal Victor and Generals Grouchy and Cambronne.

- Allied Army: 5,000 soldiers.

Aerial Panorama

At the Battle of Craonne, Napoleon seized the opportunity to win a new tactical success over Bluecher's Prussians. However, his situation did not improve, as the victory proved costly in men against the Allies firmly established on the plateau overlooking the village of Craonne.

The general situation

In keeping with the strategy adopted throughout the French campaign, Napoleon, after disposing of Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg's Austrians, turned his attention to Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's Prussians, whom he intended to corner on the river Aisne and destroy in a decisive battle.

On March 2, 1814, Napoleon crossed the river Marne at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre with this intention, but on the 3rd, the unexpected and premature surrender of the town of Soissons forced him to change his plans. The Allies took advantage of the bridge there to cross the Aisne unopposed, linking Blücher's forces with Ferdinand von Wintzingerode 's Russian corps.

On hearing the news when in Fismes , Napoleon finally decided to confront Blücher to the north of the river, crossing it in his turn. This was achieved on March 5, thanks to General Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty 's cavalrymen, who seized the Berry-au-Bac bridge, which was too weakly protected. Marshal Michel Ney's divisions and the Old Guard were the first to cross. The other corps followed, at their own pace and without any preconceived order, and advanced towards Corbeny .

As he marched towards Laon, the Emperor could not leave the left flank of his troops exposed to an attack by the Allies, who were firmly holding the plateau overlooking the village of Craonne. He absolutely had to dislodge them.

Blücher accepted the challenge. The plateau, by its very nature, was an exceptionally strong position. The field marshal stationed 30,000 men, 2,000 cavalry and around 100 cannons there, under the command of Russian general Mikhaïl Semionovitch Vorontsov (Михаил Семёнович Воронцов) .

Vorontsov was tasked with containing the French army, while a detachment of 11,000 cavalrymen under General Wintzingerode's command carried out a broad turning movement to bring them up against Napoleon's rear.

The battle

On March 6, the Imperial Guard captured the village of Craonne [49.44580, 3.78902] and the Abbaye de Vauclerc [Vauclair] [49.45260, 3.74595], but was unable to gain a foothold on the heights . Ney was also driven back after fierce fighting for possession of the Heurtebise [Hurtebise] Farm [49.44129, 3.73867].

In the evening, the French bivouacked at the foot of the plateau, around which they formed a vast arc, with headquarters at Corbeny.

The battle plan for the following day called for a simultaneous attack by Ney and Nansouty on both flanks of the enemy, the first via Ailles , the second via Vassogne and the Oulches glen, while the artillery would pound the enemy head-on.

The maneuver was a tricky one, as the attack would take place at the bottom of two ravines. In addition, the ground was frozen and the river Lette [now the Ailette] flooded, factors which were unfavorable to cavalry and artillery movements.

The Russians, for their part, organized themselves in three lines blocking the "chemin des Dames" at Ailles, front and artillery facing Hurtebise Farm , the wings leaning on the Vauclerc and Oulches ravines and protected by batteries of 12. General Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken 's troops were holding back near Cerny .

On March 7, at around 10 a.m., the French artillerymen, unfortunately inexperienced and therefore clumsy, went into action. Despite the efforts of General Antoine Drouot , who showed them the maneuver himself, the results of the cannonade were meager. Marshal Ney found himself facing untested troops at the moment of the assault, and his impetuosity led him to attack prematurely. He was unable to gain a foothold on the plateau, and settled halfway up the slope, in a critical position. He needed reinforcements. Napoleon sent them as they arrived from Berry-au-Bac.

At the end of the morning, the Russians finally gave ground to the young guard, led by Marshal Victor, who emerged with artillery from the defile leading from Vauclerc Abbey to Hurtebise Farm.

After setting fire to the farm, they evacuated it and withdrew to their front line. The French are on the plateau .

The French were subjected there to a violent bombardment, during which Marshal Victor, duke of Belluno was wounded, but held their ground despite their inexperience and considerable losses. They were soon reinforced by a thousand dragoons led by General Emmanuel de Grouchy. For his part, Nansouty managed to establish himself on the plateau and cut into the Russians' right flank, pushing it back as far as Paissy .

But the allied center was still intact and they found the energy to counter-attack. The French cavalry was driven back, Grouchy wounded, and panic gripped Ney's Marie-Louise (these were conscripts of the 1814 and 1815 classes, called up in advance in 1813, most of whom were still beardless, hence the feminine nickname), who had suffered enormous losses. They tumbled down the ravines they had struggled to climb out of just a few hours earlier. Once again, the reinforcements sent had a salutary effect.

Marshal Victor's infantrymen, commanded by General Henri-François-Marie Charpentier , reached Ailles along the edge of the Bois de Vauclerc , at the foot of the plateau, to escape enemy fire.

The first regiment of the Éclaireurs de la Garde Impériale (Imperial Guard Scouts), a new cavalry corps under General Louis Marie Levesque de La Ferrière and then Colonel Claude Testot-Ferry, was sent to support the infantry in the Vauclerc ravine. Under their joint impetus, the retreating troops rallied and began (for the sixth time since the previous day) to climb the steep slopes of the plateau.

Soon the artillery of the Guard, made up of experienced soldiers, and then that of the reserve, arrived on the battlefield via the Hurtebise defile. Their fire was directed by Napoleon himself, from the Buisson-Coquin mound . It was around two o'clock.

At the same time, Blücher realized that the cavalry maneuver he had entrusted to Wintzingerode, which, if successful, could have dealt Napoleon a fatal blow, had failed. The allied corps was unable to reach the flank of the imperial army in time, due to the state of the roads and its unfamiliarity with the terrain. Some of its troops even got completely lost. The Prussian field marshal therefore ordered Voronzov to fall back towards Laon .

Although in a very bad position (his left pressed by Ney, his right overwhelmed by the dragoons, his center gradually giving way under the blows of the French infantry and artillery), the Russian general forced his commander to reiterate his order before complying.

He then led a methodical retreat towards Cerny and, despite constant harassment and a fifteen-kilometer-long pursuit to the Ange Gardien junction , managed to avoid a rout, thus limiting his losses. He then headed for Laon via the Urcel and Chavignon defiles.

The outcome of the battle

This victory was by no means indisputable, since it was so costly - 8,000 men - that it actually constituted a strategic success for Bluecher, even if he did not achieve all his goals.

The French army emerged even weaker, unable to achieve the decisive success that was becoming increasingly essential.

For the Allies gathered around Laon, the road to Paris was still open. A new battle was needed to block it.

Map of the battle of Craonne

Picture - "The Battle of Craonne". Painted by Théodore Yung.

A monument erected at the end of World War I near Hurtebise Farm combines the Marie-Louise of 1814 and the "Poilus" of 1914-1918 in a single tribute to the heroes who fell in defense of the homeland.

On the site of the former Vauclair Mill [49.44000, 3.76470], from which the Emperor watched the fighting, a mound has been erected, topped by a statue of Napoleon by Georges Thurotte, inaugurated in 1974.

The villages of Craonne and Ailles were totally destroyed a century later, during the First World War. The former was rebuilt a few hectometres below, while the latter was not, the commune being merged with that of Chermizy.

Pronunciation: Craonne is traditionally pronounced [kʁan]. Since 1917 and the Chanson de Craonne (a French protest song) where two syllables were necessary for the meter of the verse, the pronunciation [kʁaɔn] has also existed.

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.