The Imperial University

Establishment of the Imperial University and organization

In Napoleon Bonaparte's view, education was the exclusive responsibility of the state. From the early years of the Consulate, he planned to bring all public education under a single structure. The law of May 11, 1802, which established high schools, was still quite far from this ideal. Primary education was left to the municipalities – under the supervision of a sub-prefect, however. The first level of secondary education, soon to be called collège, could either remain the responsibility of the municipalities or even be concessioned to the private sector.

Antoine-François Fourcroy, after actively participating in the drafting of this law and presenting it to the Legislative Body, became the Emperor's main collaborator in this undertaking to reorganize education, which was particularly close to the sovereign's heart. The subject offered Napoleon an opportunity to give his regime a distinctive character. As he would say a few years later: literature, science, and higher education are among the attributes of the Empire that distinguish it from military despotism

.

The first step was to organize the personnel responsible for this particular mission. On May 10, 1806, a law was enacted relating to the formation of a teaching body, under the title of Imperial University. The three articles that comprise it provide for the creation of a body exclusively responsible for public education in the Empire. Its members would enter into civil, special and temporary obligations, about which no details were given, so that it was in fact the decrees of March 17 and September 17, 1808, that gave the institution its final shape by organizing the centralization of the education system, which was necessary for its rationalization.

The Imperial University became responsible for public education in the Empire. In principle, it was administratively autonomous, under the direction of a grand master assisted by a chancellor and a treasurer. All three were appointed and could be dismissed by the Emperor. The University's management also included inspectors general, who were appointed by the Grand Master, and a council of thirty members, of which he was a part, as were his two immediate subordinates.

There was now only one teaching body. Not all of its members were civil servants, but all of them, regardless of their status, had obligations to the state. The decree of March 17 contained a comprehensive disciplinary system that provided for graduated penalties ranging from suspension to dismissal.

To run this institution, the Grand Master had a large central administration at his disposal. It consisted of the Grand Master's private secretariat, a chancellery, a general fund, a division responsible for educational matters, divided into three offices, and another for financial affairs, which comprised four offices. An architect, an engraver, and a printer completed the team.

Closer to the ground, the rectors, assisted by inspectors and a council of ten members appointed by the Grand Master, managed the thirty-two districts (called academies) into which the territory of the Empire was divided.

University officers could not hold any other public or private office without the Grand Master's consent.

The founders of this administration did not forget to provide it with the substantial resources needed to keep this great ship afloat. 400,000 francs of income were allocated to it, by entry in the public debt ledger. It also collected fees for examinations and the awarding of degrees, and was authorized to receive donations and bequests. Finally, one-twentieth of the fees paid by each student in every school throughout the Empire was allocated to it.

The system was reformed by imperial decree on November 15, 1811. The main reason for this was the continued development of private education, as well as what the Emperor considered to be the excessive proximity between Fontanes and Catholic secondary education. The State took this opportunity to recover certain prerogatives granted to the University and took advantage of it to set stricter limits on private secondary education.

However, despite its size and the extent of its prerogatives, the Imperial University remained under the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior, and its head was never considered equal to a minister. Napoleon reminded the Grand Master of this on several occasions.

The different types of institutions

All educational institutions in the Empire were either directly managed or controlled by the Imperial University. They were divided into the following categories:

- Primary schools

These taught reading, writing, and basic arithmetic. A decree of 1811 indicated that care must be taken to ensure that teachers did not take their teaching beyond.

They remained the responsibility of the municipalities, which could group together to open them. Mayors and municipal councils choose the teachers, whom they must house, and set their salaries. However, these were paid by the families. They were often too low to ensure high-quality recruitment and forced teachers to resort to private lessons to supplement their income. These reasons explain the insufficient development of this level of education.

At the end of the Empire, there were 31,000 schools with approximately 900,000 students. This represented only 25% of the age group concerned by these schools.

- Boarding schools

They belonged to independent teachers who provided a less rigorous education than that offered by institutions.

- Institutions

These were schools run by private teachers, and the level of education provided was similar to that of middle schools.

- Colleges

These were also known as municipal secondary schools. They were established by a decree dated May 1, 1802. Pupils began learning Latin and French, as well as the basics of geography, history, and mathematics.

Their opening was subject to government authorization, renewable each year, but it could be granted to a municipality or a private individual. Initially left to the discretion of the director, the recruitment of teachers was managed from 1803 onwards by a mandatory administrative office, which included the sub-prefect, the mayor, the prosecutor, the judge of peace and representatives of the municipal council. The appointments it considers are then submitted to a higher authority: the Minister of the Interior until 1808, and subsequently the Grand Master of the University. In return for this loss of autonomy, the state granted these establishments various benefits, such as the provision of premises, free places in high schools for the best pupils, and bonuses for teachers. The same decree defined the pupils' uniform. In 1806, according to Fourcroy, there were around 750 such schools, half of which were private and half municipal, with some 50,000 pupils studying there.

In 1808, secondary schools were renamed colleges and incorporated into the Imperial University. In 1811, they were divided into two categories according to the level of education provided. At this time, the students' uniforms changed from green to blue.

- High schools

The subjects studied in college were studied in greater depth. Rhetoric, logic, and basic mathematics and physics were added.

They were created by the law of May 1, 1802, replacing the central schools established during the Revolution. The state was required to maintain one high school per appellate court jurisdiction. The subjects taught were ancient languages, rhetoric, logic, ethics, mathematics, and physics. Each high school must have at least eight teachers, a principal, a vice principal, and a prosecutor in charge of administration. They were all appointed by the government. The prefect of the department in which the high school was located chaired the administrative office, which also included the presidents of the local courts. There were 35 establishments in 1808 and 45 at the end of the Empire, including four in Paris.

Discipline was strict. Students wore uniforms and were organized into companies (with sergeants and corporals) that practiced military exercises. The best student in each company, invested with the rank of sergeant major, commanded it. From 1803 onwards, religious instruction was included in the curriculum and each school had its own chaplain.

Three sources fed into high schools: secondary schools or middle schools, whose students could be admitted after passing an entrance exam; "national students," who were recipients of state scholarships; and children of parents wealthy enough to send them to boarding school.

A decree of 1809 made minor changes to the organization of lycées. The administrative office was replaced by the academic council.

In 1811, the number of high schools planned for the empire was increased to one hundred.

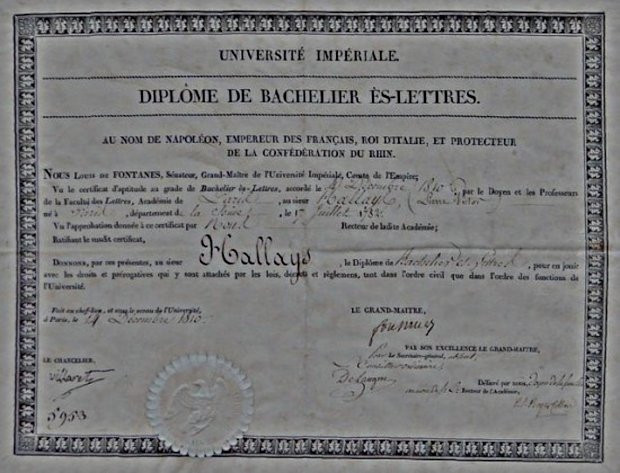

- The faculties

These replaced the special schools created by the law of May 1, 1802. They provided in-depth teaching in five disciplines: theology, law, medicine, science (mathematics and physics), and literature. They were headed by a dean, chosen by the grand master from among the teaching staff. The first professors were appointed by the Grand Master himself, but it was planned that these positions would be filled by competitive examination in the future. The baccalaureate, bachelor's degree, and doctorate were awarded by the faculties.

In 1814, the faculties had 6,131 students: more than 1,500 in law, 1,332 in arts, 1,1194 in medicine, and 326 in science.

Teacher training colleges in Paris and the departments, which were outside the general education system, trained teachers and professors. The first one opened in Strasbourg in 1810. The one in Paris had 300 students.

The main executives of the Imperial University

The Grand Master

His prerogatives were significant. He presided over the University Council. He appointed the inspectors general, the rectors of the academies, as well as the inspectors and members of the councils that assisted them. He decided on appointments and promotions to chairs in colleges and high schools, as well as to administrative positions. He placed national students (those whose schooling was paid for by the state) in high schools. The opening of educational establishments was subject to his authorization and he had the freedom to inspect them. He had the right to impose sanctions on members of the University. He ratified the results of examinations and it was in his name that degrees and titles were conferred.

He was also responsible for ensuring the proper administrative and financial management of the University. He supervised its activities, expenses, and revenues, and each year submitted several reports to the Emperor attesting to the state of educational institutions, the status of academy and University officers, and the advancement of the teaching staff.

On March 17, 1808, Louis de Fontanes was appointed Grand Master of the Imperial University. He held this position until the end of the Empire.

The Chancellor

He was responsible for the seal and archives of the University. He signed diplomas and all documents adopted by the Grand Master or the University Council. His duties included keeping a register of all University employees, both administrative and teaching staff, and presenting University members to the Grand Master for their oath of office. In the absence of the Grand Master, he was authorized to chair the council.

The chancellor appointed in March 1808 also remained in office until the end of the Empire. He was Jean-Chrysostome-Ignace de Villaret, Bishop of Casale Monferrato.

The treasurer

He is aesponsible for revenue and expenditure and, in particular, ensured that the fees owed to the University were collected throughout the Empire. He was responsible for salaries and pensions, as well as overseeing the accounts of all establishments. All these tasks were reported to the Grand Master.

Like the Chancellor, he was able to deputize for the Grand Master as President of the Council.

Napoleon entrusted these functions to the mathematician and astronomer Jean-Baptiste Delambre from 1808 until the fall of the Empire.

The Council of the Imperial University

Under the chairmanship of the Grand Master, it was called upon to rule on various matters concerning the institutions under the Imperial University: statutes, police and administrative issues, or any other matter submitted to it by its president. In addition to the president, it was composed of the chancellor, the treasurer, and nine full members and ordinary members. The latter included inspectors general and certain rectors.

All members of the council were appointed by the Emperor. Several illustrious figures would be among them: the philosopher Louis de Bonald, despite being a declared royalist, the paleontologist Georges Cuvier, the botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu The council had a general secretariat, which was responsible for drafting the minutes of the council's meetings. These minutes were then sent to the Ministry of the Interior.

The inspectors general

Their role was to inspect the various schools, complementing the work of the rectors and academy inspectors. To fulfill this mission, they were involved in evaluating students, supervising studies and discipline, assessing the abilities of both teachers and administrators, and even checking the administration and accounting.

Originally created in the number of eighteen by an imperial decree of September 21, 1808, there were twenty-six of them at the end of the Empire.

Academy rectors

Rectors were appointed by the Grand Master for a minimum period of five years, but they could be retained in office for longer. The Paris academy, due to its strategic importance, was an exception: it was administered directly by the Grand Master. Rectors were most often university professors.

Originally numbering thirty-two, as their boundaries were modeled on those of the courts of appeal, there were forty in 1813. New academies had to be created due to the territorial expansion of the Empire.

The rector wes, in his academy, the equivalent of a prefect in his department. He represented the central government and was responsible for education.

His duties were numerous: attending examinations, as guarantor of the validity of the diplomas awarded; hearing reports from the heads of the various establishments within his jurisdiction: university deans, high school principals, middle school principals; supervising these institutions from an educational, disciplinary, and financial standpoint. To carry out these tasks, he visited the institutions or sends school inspectors to assist. However, he was required to visit the high schools in his or her district four times a year and to visit the colleges regularly. Finally, he presided over the academic council and drew up the list of books authorized in the institutions.

The 1811 reform curtailed the powers of rectors in favor of prefects. The latter were now responsible for primary education and have taken over the inspection powers previously devolved to rectors.

Academic inspectors

There were one or two per academy (except in Paris, where there were five), appointed by the Grand Master on the recommendation of the Rector. While their primary focus was on financial and administrative aspects (organization, discipline, premises, and sanitary conditions), they could also examine the teaching itself. Their opinions were collected at the national level and were taken into account by the central administration in the management of teachers' careers and in any decisions to close establishments.

They were closely attached to the University and could only resign with the authorization of the Grand Master, unless they repeated their request three times. Thirty years of service entitled them to a retirement pension. They could also benefit from the University's retirement home for officers, including prematurely in the event of disability occurring during their term of office.