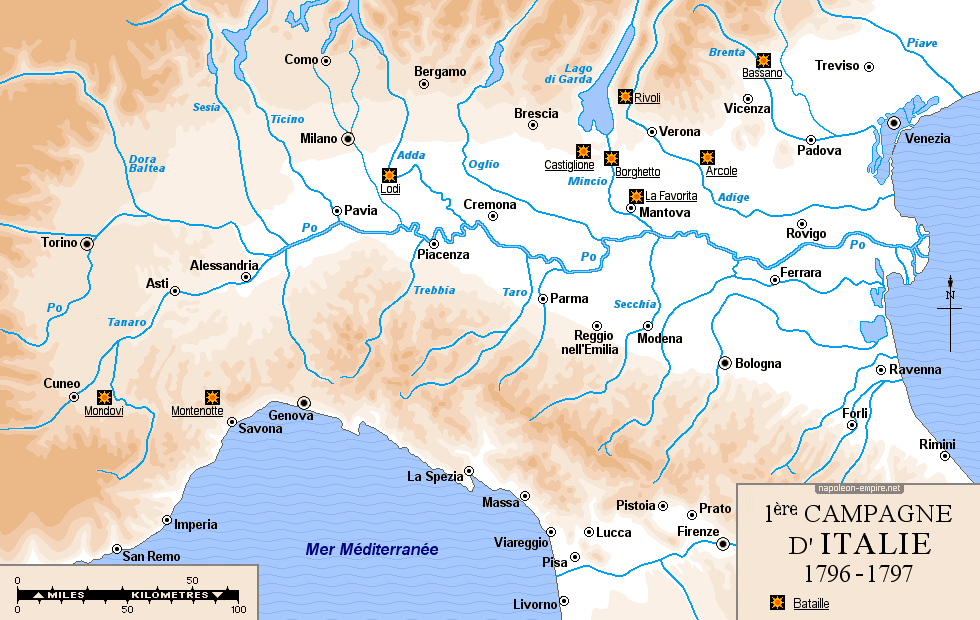

Military operations of the first Italian Campaign (1796-1797)

The Italian campaign was one of the operations of the wars of the First Coalition. Since April 20, 1792, revolutionary and soon-to-be republican France had been pitted against the monarchical powers of Europe.

At the dawn of 1796, the Republic's main adversary was Austria. It relied on the United Kingdom, which acted mainly through its fleet and finances. The Kingdom of Sardinia, whose main component is Piedmont, is allied to them. The Kingdom of Naples was technically at war with France, but gave only token support to its cobelligerents.

The conflict was taking place on two fronts: Germany, which the French Directory, in power in France since October 1795, considered to be the main theater of operations, and Italy. The importance of the latter was therefore secondary in the plan drawn up by Lazare Carnot, the Director in charge of military affairs. It was inspired by those presented by Napoleon Bonaparte over the previous two years, as head of artillery for the Army of Italy and member of the topographical bureau of the Comité de Salut Public.

When Bonaparte took command, the plan was to march on Vienna [Wien] via the Main and Danube valleys , to force Austria to negotiate. The Army of Italy was to play a diversionary role against the Piedmontese troops and the Austrian armies holding Lombardy and Milan [Milano] . As for its conduct towards the other Italian states, which oscillated between malevolent and frightened neutrality (Genoa, Parma, Modena, Tuscany, Lucca, Venice), barely disguised hostility (Papal States) and parsimoniously active antipathy (Naples, which supplied 1,500 cavalry to the Austrian army), the instructions given to its general-in-chief were silent on the subject.

In the spring of 1796, this army lacked everything: money, equipment, horses, food, except quality generals - Andréa Masséna and Charles Augereau, in particular, had already demonstrated their talent - and its soldiers were severely deprived. Napoleon Bonaparte knew how to play on this destitution to motivate his troops.

The first campaign of Italy, day after day

The first campaign of Italy, day after day

Opening of the campaign

The opposing forces

The French troops were divided as follows:

- François Macquard's (sometimes spelled Macquart) 3,700-strong division and Pierre Dominique Garnier's 3,300-strong division were positioned in the valleys leading to the Col de Tende and the Col de Cerise respectively; these two divisions liaised with the Alpine army commanded by François Christophe Kellermann;

- A 4,000-strong cavalry division was stationed on the coast;

- Jean-Mathieu Philibert Sérurier's 7,000-strong division was stationed near Ormea and the sources of the Tanaro;

- Augereau's 8,000-strong division was even further back, in front of Finale Ligure;

- Masséna's 9,000-strong division was a little further back (to the southwest), near Vado;

- Amédée Emmanuel François Laharpe's 8,000-strong division standed near Savona. One of his brigades, commanded by general Jean-Baptiste Cervoni , has advanced as far as Voltri.

These last three divisions also occupied a number of posts on the Apennine ridges around the sources of the Bormida.

All in all, this represented a strength of around 43,000 men, equipped with less than sixty cannons. Two reserve divisions (or three, depending on the author), stationed in Provence and in the annexed county of Nice, served as depots, while protecting the ports and ensuring internal security.

The French thus occupied the Genoese Riviera and the ridges above it. Such a tightly-packed position between the mountains and an enemy-controlled sea could not be maintained for long. Indeed, any adverse success on the French left would have spelled disaster, as the British fleet constantly threatened the only route across this strip of land, and thus the only available line of retreat.

On the other side, Johann Pierre de Beaulieu-Marconnay assumed superior command of both the entire Austro-Sardinian system and the Austrian army itself. The latter comprised 32,000 soldiers, divided between a right wing of 15,000 to 16,000 men under Eugène-Guillaume d'Argenteau and a left wing of 16,000 to 17,000 soldiers under Karl Philipp Sebottendorf van der Rose. The Sardinian army, under Austrian general Michelangelo Alessandro Colli-Marchi, comprised 20,000 Sardinians and the 5,000 Austrians of a liaison corps under general Giovanni Provera. These numbers, however, were largely theoretical, as the various units all had large numbers of sick men. What's more, the two main generals showed an almost total inability to get along and cooperate, largely due to the mistrust prevailing between their respective governments.

These forces were arranged as follows:

- Colli stood with the bulk of his forces (eight battalions) near Ceva, while having distributed some troops (two battalions) towards Murialto, Paressio, Mondovì and Pedagena;

- Provera was on his left, with four battalions, between Cairo [Cairo Montenotte] and Millesimo , and linked up with Argenteau ;

- Argenteau has moved to Sassello with three battalions. He held a line some forty kilometers long between Ovado, in the Orba valley, and Cairo . He had eleven infantry battalions and two cavalry squadrons at his disposal, which was only half the strength he commanded, the rest being still on the Po. As a result, his forces were excessively crumbled and dispersed, as Austrian military doctrine at the time demanded that every valley, every foothill, be held by a few men;

- The left wing had four battalions on the Bocchetta and two at Campo-Freddo, or at least on their way there.

In all, half of the Austro-Sardinian army was in contact with the French, but in extremely scattered positions with fragile communications, while the rest was in the process of concentrating towards Acqui and Novi, several days behind. It was therefore at the mercy of an energetic attack, especially as no serious steps had been taken to prepare for it.

The operational plans of the two adversaries

Curiously, both generals-in-chief intend to take the offensive.

Beaulieu wished to expel the French from the Genoese Riviera and seize the Alpes-Maritimes, which, thanks to possession of the coastline, would enable him to coordinate better with the English fleet and reduce the extent of the front to be defended. This plan hardly differed from the one implemented the previous year by his predecessor. He was only looking for limited gains at the cost, he believed, of limited risks.

Napoleon Bonaparte, on the other hand, had set himself a far more ambitious goal: to switch the Kingdom of Sardinia from its alliance with Austria to an alliance with France. The French Directory had even indicated the means: repel the Austrians, conquer Milan and offer it as a pledge to Piedmont, which had so far been spared the blows.

However, Bonaparte was not going to do this. The plan involved bringing all his forces to bear against the Austrians, neglecting the Sardinians. This would mean putting himself at the mercy of the Austrians, who, benefiting from their geographical position, would only have to make a minimal effort to cut off his communications with France and move in on his rear. But if he were to leave a sufficient detachment in front of them to deal with this eventuality, success against Austria would become problematic, as the manpower available against this adversary would no longer be sufficient. Moreover, Sardinian troops were both less numerous and less solid than Austrian ones, and their proximity to Turin [Torino] would force their government to deal with defeat without delay. Separating Beaulieu and Colli, and then focusing all efforts on the latter, was therefore the main focus of the Army of Italy's maneuvers.

From Montenotte to Mondovì

Bonaparte, who had arrived in Nice on March 27, was in Savona on April 9, having followed the Corniche route with his entire staff under fire from British ships. He wanted to take the offensive immediately, crossing the mountains at the junction of the Alps and the Apennines, at the source of the Bormida.

Almost simultaneously, Beaulieu, having rejected a plan proposed by General Colli that was bolder than his own, launched his own attack, aimed exclusively at the French right wing. In this way, he hoped to cut off Genoa and link up with British Admiral John Jervis's fleet, without endangering himself by attacking the bulk of the enemy forces. With these limited objectives in mind, he did not even consider it necessary to complete the concentration of his troops before taking action.

The first battle took place at Voltri on April 10. The French extreme right, under Cervoni, attacked by two columns totalling 8,000 men, was repulsed with some losses. It retreated towards Savona and then La Madonna de Savone, where it joined the Laharpe division the following day. On the 11th, Argenteau began to carry out the order he had received on the 9th to advance to Montenotte and drive the French from the surrounding heights. At first, he encountered little resistance. But when he came up against colonel Antoine-Guillaume Rampon and the two battalions of the Laharpe division installed in the abandoned entrenchments crowning Monte Legino (or Monte Negino) , all his efforts were thwarted by the determination of the French. By nightfall, he could only withdraw his troops.

In view of these movements, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to move on Argenteau with the Laharpe, Masséna and Augereau divisions, a total of around 25,000 able-bodied men. He intended to crush the enemy with his numerical superiority and separate the two wings by knocking down the center. Meanwhile, Sérurier was sent to Ceva through the Tanaro valley to secure Colli.

During the night of April 11th to 12th, Laharpe climbed Monte Legino and attacked Argenteau head-on in the early hours of the morning. Masséna, accompanied by Bonaparte, passed through Altare and outflanked the Austrian right flank. Augereau, describing an even wider loop, moved on to Cairo , then turned right to reach the combat zone. Although the last of these divisions, having further to go, arrived too late to take part in the battle, these combinations resulted in 15,000 French attacking 4,000 Austrians. Argenteau barely escaped towards Ponte Ivrea [Pontinvrea] through the Erro valley, leaving 2,000 to 3,000 men behind. He then retreated to Paretto, near Spigno.

Having reason to believe that the bulk of the enemy troops were at Sassello and Dego , Bonaparte took the following steps:

- Laharpe advanceed towards Sassello to focus attention on him. He would then fall back on Dego and take part in the attack there;

- Masséna moved to Dego , which he was to attack on the 13th with Laharpe's support;

- Bonaparte and Augereau marched on Carcare .

On the 13th, however, Masséna, who did not see Laharpe arrive as expected, considered himself too weak to attack Dego alone, and was content to send a few men to reconnoiter while his division held out at La Rochetta.

On the same day, with Augereau having taken control of the area around Millesimo, Napoleon Bonaparte attacked General Provera, who was holding out at Cosseria with 1,800 men, with two brigades. Deprived of a line of retreat by the movements of the French, he threw himself into the old ruined castle of Cosseria , clinging to a rocky outcrop between the two Bormida mountains and difficult to storm despite its condition. Night fell with no significant change in the situation, despite a few rescue attempted by Colli. He had to resign himself to seeing his left wing driven out of its positions and besieged. Once again, Bonaparte's combinations enabled the French to fight with a large numerical superiority: 8 to 10,000 of them facing 3 to 4,000 coalition troops.

Meanwhile, Argenteau, having received orders to do all he could to hold Dego, sent Colonel Joseph Philipp Vukasović (Wukassovitch) there with five battalions, while Beaulieu marched three more through Spigno.

Leaving Augereau in front of Provera, which soon surrendered for lack of food and water, costing the Austrians an additional 2,000 to 3,000 men, Napoleon Bonaparte marched on Dego on the 14th. He led an energetic attack, enthusiastically executed, which resulted in the capture or destruction of seven battalions and eighteen cannons. Argenteau, deceived by false news of Masséna's retreat, left Paretto too late, to the sound of cannon thundering on Dego, and arrived only to witness the fall of the fortress. He retreated to Acqui [Acqui Terme] with the remnants of the garrison who had managed to escape.

Colonel Wükassovitch has not yet arrived. The victim of a chronological error on the written order he had received, he remained inactive for most of the 14th and only approached Dego on the 15th, informed that the French had taken the place. He attacked them, however, and was initially successful. His opponents were limited to a fraction of the Masséna division (around 6,000 men, the rest having gone against Colli), who were also convinced that they were being attacked by the entire Beaulieu corps. Such was the French stampede that Masséna was unable to overcome it, and the Austrians took control of the entrenchments. Bonaparte, however, also believing in Beaulieu's attack in force, turned back from Carcare , where he had spent the night, and returned to Dego with the Laharpe division and the Claude-Victor Perrin, known as Victor brigade. This time, Vukassovich, unable to find any reinforcements in the vicinity (there wasn't an Austrian battalion within twenty kilometers), had to give in to his numbers. He withdrew to Acqui, having finally lost half his force. At Dego again, the French managed to muster 15-20,000 men against 4,000 Austrians.

Taken together, these battles, known as the Battle of Montenotte, cost the coalition some ten thousand men and perhaps forty cannons. Such results, achieved in the end mainly by the two divisions Masséna and Laharpe and the Victor brigade, a total of 20,000 men, could never have been achieved in pitched battle and were essentially the result of the quality of the combinations executed. Clausewitz did not hesitate to say that, in this case, strategy alone almost decided the outcome.

Bonaparte, thus established, as desired, between the two enemy armies, now attacked the Sardinians before they knew the full extent of the defeat of the rest of the coalition army. Leaving Laharpe to observe the Austrians, he turned towards Colli with the Masséna, Augereau and Sérurier divisions.

Immediately after Provera's surrender, Augereau headed for Montezemolo and drove Colli back to Ceva. On April 16, he was in front of Ceva. Sérurier then joined him after descending the Tanaro valley, where he had been positioned since the start of the campaign. Colli divided his 15,000 men between Ceva (8,000), Pedaggera (4,000 to the north) and Mondovì (3,000 in reserve). On the 19th, Augereau attacked at Ceva and Pedaggera, while Sérurier turned the enemy to his right at Mombasiglio and Masséna to his left at Castellino Tanaro. The Sardinians held out bravely in the Ceva redoubts, but could only escape the turning movements that threatened to surround them by retreating to the Cursaglia river, in a position made very strong by its steep banks. Their right was at Madonna de Vico, their center at San Michele Mondovì, and their left near Lesegno.

Napoleon Bonaparte gave the order to attack without delay. But neither Augereau nor Masséna succeeded in crossing the river, and Sérurier, who did manage it, was driven back to the other bank with heavy losses. Only one brigade, commanded by General Jean Joseph Guieu (or Guyeux), crossed the Cursaglia above Torre Mondovì and pushed back the Sardinians' right. This was not enough to prevent the battle from being a French failure.

Five days after Dego, it was feared that Beaulieu would once again be in a position to intervene. This was what the Austrian ambassador had promised the Turin court, and what Bonaparte was expecting. With the French troops exhausted and somewhat demoralized by their failure at the Cursaglia, the situation became delicate. Napoleon Bonaparte convened a council of war at Lesegno . It was decided that neither the fatigue nor the discouragement of the troops should delay a new attack. Circumstances could only become more and more unfavorable, and immediate action was needed to avoid being rapidly driven to defeat.

The following arrangements were therefore made for the attack on April 22nd :

- Sérurier would attack the right wing;

- a new provisional division of two brigades, under General Philippe Romain Ménard, would move to the center against San Michele Mondovì ;

- the brigade of Barthélemy Catherine Joubert's would oppose Colli's left wing;

- Augereau would attempt to cut off enemy communications at Castellino.

General Colli, who had no hope to resist if the French sought decisive action, could only expect an improvement in his situation through combined action with Beaulieu. His only concern was to gain time while waiting for this. On the night of the 21st, he moved to a new position in front of Mondovì, one or two kilometers further back, which seemed likely to allow him to wait for help for a few days.

Unfortunately for the Sardinians, when the French realized they were attacking an abandoned position, they immediately gave chase. Sérurier and Ménard were the first to make contact. Colli's troops, who had not retreated quickly enough, were joined near Vico [Vicoforte] and were already in confusion by the time they reached their destination, where they were immediately attacked by the French. The center held out for a while on the Bricchetto but, surrounded, eventually gave in. Colli withdrew through Mondovì . He lost 1,000 men and 8 artillery pieces, but managed to inflict serious losses on the French cavalry, which prematurely charged its own during the withdrawal.

This defeat and the fact that little help could be expected from their Austrian ally demoralized the Sardinian troops and authorities. As early as April 23, the Sardinian government expressed its desire to conclude an armistice. As this request was perfectly in line with French interests, Bonaparte was careful not to set too harsh conditions. He simply asked for two places to be chosen from among Alessandria , Tortone [Tortona] and Coni [Cuneo], with a view to using them as bases for future operations.

Pending Sardinia's response, Napoleon Bonaparte sent his army across the Ellero on April 23. The following day, Serrurier headed for the Trinité de Fossano, from where he moved on to Fossano on the 25th, occupying it after exchanging artillery fire with Colli. The same day, Masséna entered Cherasco and Augereau Alba. Laharpe remained at Benedetto. On the 26th, Masséna and Augereau joined Serurier, while the town of Cuneo was taken. Bonaparte was now firmly entrenched between Colli and Beaulieu.

Following the news of Mondovì and the Sardinians' request for an armistice, the Austrian general-in-chief decided not to take steps to unite the two coalition armies towards Alba, while Colli continued to retreat towards Turin. On the 26th, Colli was in the vicinity of Carmagnola.

On the 28th, the Sardinian government signed the Cherasco armistice, considering that the French were only two steps away from Turin, that a republican party was beginning to emerge in the capital and that the spirit of the army was giving it cause for concern. Piedmont-Sardinia withdrew from the conflict.

The fall of Milan and Lombardy

With the defection of the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Austrians' situation in Italy became extremely precarious. The French were now in a position of numerical, moral and even political superiority, as the various states of the peninsula were forming powerful parties sympathetic to the new ideas, which they hoped would lead to an Italian renaissance. Under these conditions, the Austrian army's attempt to hold on to the upper course of the Po was clearly too onerous a task. It would only lead to further defeats. Yet this was the mission his government ordered Beaulieu to undertake. Beaulieu crossed the River Po and set up the bulk of his troops at Valeggio [a village in what is now the province of Pavia] and Lomello. His left wing was at Sommo, between the river Ticino and the Po, with a few outposts on the river, which they guarded as far as Olona; his right wing was on the Sesia. The choice of this disposition was essentially motivated by the (theoretically) secret clause that Napoleon Bonaparte had included in the Cherasco armistice to give him authorization to cross the Po at Valenza.

Napoleon Bonaparte resumed the offensive at the beginning of May 1796, before the arrival of Austrian reinforcements. Given the current state of forces, the choice of where to cross the Po was entirely up to him. It would be the result of a balance between practical constraints and strategic imperatives. The first and most important difficulty was the lack of bridge equipment. It imposed the use of the means available at the crossing point and therefore prohibited the choice of one that was seriously defended. Secondly, while a crossing far to the east would have the double advantage of driving the Austrians away from Milan and sparing the French army the crossing of several tributaries on the left bank of the Po, it could not be made close enough to the Adriatic to push Beaulieu directly back beyond the Adige . In any case, it would be necessary to penetrate Lombardy and take the various strongholds there.

Napoleon Bonaparte finally decided to cross a little downstream from the point where he was determined to lure Beaulieu. A few demonstrations in the latter zone completed the effect of the armistice's hidden clauses. While the Austrians were focused on this point, a French detachment would be sent to move a little further east. The rest of the army would follow immediately. In this way, it would be impossible to cross further than Piacenza. The French army would therefore gain a foothold on the left bank of the Po before the river's confluence with the Adda, which was a drawback; the counterpart would be to be able to count on the effect of surprise.

On May 4, the French divisions were positioned as follows:

- Serurier at Alexandria and Valenza;

- Masséna at Tortone and Sale ;

- Augereau at Castellanio ;

- Laharpe at Voghera and Casteggio.

Everything seemed to confirm that the Po would be crossed at Valenza. But on May 6, Napoleon Bonaparte, with 3,000 grenadiers and 1,500 cavalry, headed for Piacenza on a forced march. On the 7th, he crossed the river using boats found on the right bank. The two Austrian squadrons holding the other bank were repulsed. The rest of the Italian army began to cross the same day, but it would take two more days before the limited resources available would allow it to be assembled on the left bank.

In the meantime, Beaulieu made a few rather disorganized moves, which nevertheless brought General Anton Lipthay (or Liptay) of Kisfalud and his 8,000 men into contact with the French on the left bank on the evening of the 7th. Liptay, however, did not dare to attack them fully and withdrew to Fombio. The next morning, Napoleon Bonaparte, leading 10,000 to 12,000 men in three columns, attacked. Two flanking columns set out to cut him off from Casal Pusterlengo on one side, and Codogno and Pizzighettone on the other. The third attacked head-on. Lipthay managed to withdraw after losing 600 men, pursued to Codogno by Laharpe and then towards Pizzighettone by Claude Dallemagne.

At almost the same time, Beaulieu, informed of the fight on the 7th, set off towards Ospedaletto, with the intention of joining forces with Liptay to drive the French back to the other bank of the Po. In the evening, despite the news of his lieutenant's defeat, he decided to continue his movement and join him first thing the next morning. That same night, General Laharpe was accidentally killed by his own soldiers during an attack on his division towards Codogno. The success of this small engagement reinforced Beaulieu's offensive plans. He decided on a general assault on Codogno, sent out the necessary orders and then, realizing that they could not reach Liphay, finally gave up. From now on, he would concentrate on bringing his army back behind the Adda. Colli (who had been relieved of his command by the Cherasco armistice and was now at the head of a division of Beaulieu's army) was ordered to leave a garrison in the Milan citadel and cross the river at Cassano, while Sebbotendorf was ordered to join Wukassovitch and move as quickly as possible to Lodi to cross the Adda. On the 9th, Beaulieu took the same direction.

On May 10, French artillery and cavalry finished crossing the left bank of the Po (a bridge was finally available that day). During the day, Napoleon Bonaparte set off for Lodi. He took only grenadiers with him. Masséna's division followed, Augereau's was a little behind. The Laharpe division, entrusted to General Ménard, remained at Pizzighettone. Sérurier marched on Pavia, with orders to push on to Milan.

Once in Lodi, Beaulieu left General Anton von Schubirž von Chobinin there to wait for Sebottendorf and himself immediately continued on his way to Crema. Once Sebottendorf arrived (and Schubirts had left to join his commander-in-chief), 12,600 men remained on site. They were not supposed to stay there for more than a day. Their mission was simply to provide the rest of the army with a respite so that it could rest after the forced marches of the previous days.

Despite the number of defenders and the length of the bridge (some 200 meters) , which everyone agreed made the position impregnable, Bonaparte, after a few hours of fighting, decided to storm the bridge. The Austrian troops, frightened by the recklessness of their attackers and probably already devastated by the defeats they had suffered in the previous weeks, gave way to the French grenadiers and then to the Masséna and Augereau divisions.

Sebottendorf, who lost 2,000 men and 15 cannons in the process, rallied at Fontana , withdrew to Beuzona and reached Crema during the night, undisturbed by the French.

After this unprecedented feat of arms, whose repercussions were immense in Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte spent four days in Crema. He received a communication from the Directorate announcing that the government intended to reinforce the Army of Italy with troops from the Army of the Alps, but also to split it into two equal parts. The first, commanded by François Christophe Kellermann, would continue to operate in northern Italy, while the other, entrusted to Bonaparte, would descend into the peninsula to drive the English out of Livorno and force Rome and Naples to sign the peace treaty. Napoleon replied on the 14th with a polite refusal, arguing that this division of command would be a mistake and putting his resignation on the line. On receipt of his letter, the French Directory abandoned the project.

Meanwhile, Beaulieu retreated through Pizzighettone and Cremona towards the Oglio, which he passed on May 14th. He then withdrew behind the Mincio via Mantua [Mantova]. Rather than pursue him vigorously, Napoleon Bonaparte chose to secure Milan.

With the Austrian garrison at Pizzighettone having surrendered, the Masséna and Augereau divisions marched on Milan, while Sérurier monitored the Austrian retreat from Cremona. While the Laharpe division was no longer mentioned in the reports, its strength having probably been divided between the other three, Augereau secured Pavia with a garrison of 300 men, then joined Masséna in Milan on May 14. Napoleon Bonaparte in turn entered the Lombard capital the following day and tasked General Hyacinthe François Joseph Despinoy with reducing the citadel, where the 1,800 to 2,500 soldiers left behind by Colli were still holding out.

The general-in-chief devoted the following days to administration and diplomacy, while his troops enjoyed their first relaxation since the start of operations for eight days.

On May 23, they were gathered around their commander on the Adda when he learned of the unrest in Milan, and that the French army was threatened by an uprising in its rear. The main causes were bad behavior ot the troops, heavy requisitions, deafening clergy and rumors of major reinforcements for Beaulieu as well as an English landing at Nice. A few disturbances were reported in Milan, but it was in Pavia that the situation was most serious. Thousands of armed peasants seized the castle after neutralizing the French garrison.

Bonaparte's first concern was to re-establish the situation in Milan, to which he returned immediately. This he did on the evening of the 24th. He then took the road to Pavia at the head of 1,800 men. On the 25th, he dispersed a gathering of armed peasants in Binasco and had the village burnt down. On the 26th, he reached his objective and recaptured the city, but not without a fight. Napoleon Bonaparte's severity was felt both by the French soldiers - a tenth of the garrison and its commander, who had surrendered without a fight, were shot - and by the insurgents - a few houses were burnt down and the town left to loot for a few hours. Once calm had returned, the army turned back towards the Austrian enemy and headed for Brescia, arriving on the 27th.

Crossing the Mincio

Beaulieu was determined to defend the Mincio line. Including the Mantua garrison, which had grown to 13,000 soldiers, he had 31,000 men at his disposal. A few thousand were rather uselessly stationed on the shores of Lake Garda , towards Riva and as far as the sources of the Adige. The rest were distributed as follows:

- Liptay, with 4,500 men, formed the right wing. He was based towards Peschiera, with his vanguard on the Chiese, a tributary of the Po that flows from the north, on the west of Lake Garda;

- Sebottendorf, with 6,000 men, held the center at Valeggio sul Mincio ;

- Colli, with 9,500 men, half of them taken from the Mantua garrison, occupied the left wing at Goito;

- Michael Friedrich Benedikt von Melas, with 4,500 men, commanded the reserve. He was stationed at Oliosi;

- Beaulieu's HQ was at San Giorgio, near Borghetto;

- Mantua was held by 8-9,000 men, half of whom were detached to the Chiese and Po rivers;

- A number of outposts on the right bank of the Mincio rounded off the operation.

Napoleon Bonaparte decided to cross the Mincio at Borghetto . The bridge at Borghetto was not destroyed, nor were the other three bridges on the river. Better still, it was defended by only one battalion and one artillery piece, the Austrians having, as usual, spread their forces too thinly.

On the morning of May 30, the French managed to cross the river. The enemy retreated to Castelnovo for Beaulieu, Mélas and Lipthay, and to Villafranca [Villafranca di Verona] and Bussolengo for Sebottendorf. Colli, for his part, sent his infantry back to Mantua before joining Liptay with his cavalry. The pursuit, however, lacked Napoleon Bonaparte's usual zeal to exploit his advantages. His indisposition on the day of the battle, or, more likely, the fatigue of his troops, explain this unusual sluggishness. Masséna, however, advanced as far as Rivoli Veronese , following the Austrians into the Adige valley . Beaulieu retreated to Calliano, beyond Trento, and dispersed once again from the Grisons to the Brenta valley.

Beginning of the Mantua blockade

Having pushed its opponents back as far as the Tyrol, the French army set out to protect its conquests and complete them by taking Mantua before the arrival of an Austrian relief army. To achieve this, Napoleon Bonaparte had to gain control of the Adige line by controlling the Verona and Legnago bridges. On June 3, 1796, he sent Masséna to seize the first of these towns. Porto-Legnago was similarly occupied, and an army of observation positioned itself from Monte-Baldo to the lower Adige, via Verona. The siege of Mantua was thus covered. Napoleon Bonaparte himself went there with Sérurier and Augereau.

The Mincio River formed three lakes surrounding the city. The town was connected to the mainland by five dikes cut by drawbridges or gates, of which only one, the Favorite, was protected by a citadel. On June 4, Napoleon Bonaparte took control of the other four exits after some fierce fighting. He then put Sérurier in charge of the blockade, assigning him 8,000 men - almost half the number of those under siege, but enough given the configuration of the site. Convinced by his engineers that the fortress could not hold out for long, Bonaparte did not establish any circumvallations, which proved to be a mistake when Dagobert Sigismund von Wurmser took refuge in the fortress after the battle of Bassano.

During the following weeks, while Masséna and his 12,000 men continued to guard the Adige valley, Bonaparte was busy organizing the occupied territories, the siege of Mantua, diplomacy and minor military expeditions in the south of the peninsula. He took this time because he knew perfectly well that he had it.. Beaulieu was stuck waiting for 30,000 reinforcements to be sent from Germany, none of which had yet set off and none of which could reach their destination in less than six weeks - two circumstances of which the French general staff was well aware.

In the first days of June 1796, the occupied regions once again experienced a degree of unrest. These disturbances were severely repressed, and the Senate of Genoa, in whose territory they had occurred, was strongly urged not to tolerate any further unrest. The King of Naples, for his part, prudently drew the consequences of the defeats at Beaulieu by sending armistice proposals on the 5th.

To convince Pope Pius VI to be as wise as his southern neighbor, Augereau marched to Bologna with 10,000 soldiers. He crossed the Po on June 14 and took the city on the 19th. His general-in-chief joined him almost immediately. The demonstration was sufficiently convincing for a Papal plenipotentiary, the Marquis Antonio Gnudi, to sign an armistice on the 23rd, which cost his sovereign 21 million francs, 100 works of art and the occupation of Bologna, Ferrara and Ancona until peace. Three days later, Bonaparte left Bologna for Pistoïa with the Charles-Henri de Belgrand de Vaubois division (recently arrived from the Army of the Alps), then pushed on to Livorno, where he seized English goods. Vaubois and Augereau then set off again for the Adige, having left a few garrisons behind in Livorno and Ferrara among other places. However, the mood there was so resolutely in favor of the new ideas that the national guards these towns were equipped with would suffice to ensure French domination.

Meanwhile, Sérurier, with 10,000 soldiers, continued the blockade of Mantua. The city was well supplied with men (13,000), cannons (316) and food, and was under the command of a renowned military officer, General Josef Franz Canto d'Irles, whose main concern was the very high number of sick in the garrison: almost 4,000. At the end of June, the arrival of Augereau gave the French the opportunity to finally begin a proper siege, with reinforced troops. However, as Wurmser had in the meantime left for the Tyrol, the question arose as to whether it would be wise to undertake this work before the coming fighting. Napoleon Bonaparte was won over by the assurances of his engineers, who predicted a rapid fall of the town. Construction began on July 18.

Wurmser's first offensive

Although Beaulieu had already given way to General Mélas in June, it was Wurmser who was finally appointed his successor, leading a 29,000-strong reinforcement from the Haut-Rhin into the Tyrol. The addition of these forces to those already at the front and a few other reinforcements from other parts of the Austrian monarchy will bring the total number of men under his command to over 60,000.

Austrian campaign plan

Wurmser's plan was to break out of the mountains on both sides of Lake Garda. A first column of 32,000 men, under his own command, would march down the Adige valley. A second column of 18,000 soldiers, under the authority of Peter Vitus von Quasdanovitch, would arrive via Riva and Salo, to the west of the lake. The maneuver had several aims: to secure the route of forces too large to use a single road; to get the French to divide up too, as their line of retreat was threatened; to clear Mantua almost mechanically; and to make the most of the consequences of the victory on which they were counting in the event of a general battle, which, coupled with possession of Mantua, would free Milan. As Napoleon says in his Memoirs: Wurmser was not thinking of winning, but of taking advantage of his victory and making it decisive and fatal for his enemy.

And Clausewitz adds: (...) we have no hesitation in regarding the Austrian plan as one of those strategic conceptions in which a false staff science feels the need to combine forces and directions without even knowing why.

On the French side, Pierre François Sauret de la Borie (known as Sauret) formed the left wing with 4,000 to 5,000 men positioned on the western shore of Lake Garda and in the Chiese valley. He was therefore on Quasdanovitch's route. On Wurmser's road stood Masséna, who commanded 15,000 to 16,000 men from his headquarters at Bussolengo, between Rivoli Veronese and Verona, guarding the main points of the Adige. To his right, General Despinoy watched over the river from Verona to Zevio, at the head of a reserve of 5,000 infantrymen stationed around Peschiera. Further out, Augereau, with 5,000 to 6,000 men, was stationed at Legnago, guarding the river on either side of the town. The cavalry reserve (15,000 to 16,000 horses) was at Valèze [Valeggio sul Mincio]. All in all, around 33,000 men, capable of assembling in two days, whether in the east between the Mincio and Adige rivers, or in the west between the Mincio and Chiese rivers. In front of Mantua, Sérurier held on to 10,000 men and his immobility.

Austrian successes

The first skirmish took place on July 29 at Rivoli Veronese , a position that the terrain made very difficult to defend against numerically superior forces. Napoleon Bonaparte, therefore, did not expect Masséna to make a stubborn defense, but simply to gain the time needed to assemble the French forces and allow them to offer combat in a place chosen by their general-in-chief. Wurmser presented himself split into two main columns and three secondary columns, on a front 20 kilometers wide. What might have cost him dearly against the bulk of the French army, he found harmless against the 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers stationed opposite him. In these conditions, on the contrary, with less than one man against two, it was the defenders who could be in great peril if they resisted too hard. Wisely, Masséna defended only long enough to gather his outposts, then withdrew. This prudent course of action was not without substantial losses in men and material. Shortly before nightfall, his division reached Pioretano.

Also on the 29th, Quasdanovitch repulsed General Sauret's French troops from Salo. A French battalion and General Guieu managed to hold out, however, entrenched in a large building outside the town. Quasdanovitch then advanced as far as Gavardo, and one of his detachments captured several troops and generals in Brescia. Sauret had to retreat to Desenzano.

When he received reports of these engagements, in which the enemy's forces may have been overestimated, Napoleon Bonaparte deemed it essential to proceed with a general concentration of his forces. On the evening of July 30, after consultation with his generals (which would be highly unlikely to have taken the form later recounted by Augereau, to give himself full credit for the arrangements finally adopted), he decided to lift the siege of Mantua without even taking the time to save the artillery parks, and to attack en masse one of the two enemy columns, while they were still separated by Lake Garda. The attack was to be made on Quasdanovitch, whose army was the weaker, threatening the French rear and their communications with Milan.

That day, Masséna was at Castelnovo, Augereau at Roverbello, Despinoy and Charles Édouard Jennings de Kilmaine at Villafranca di Verona. Sérurier was busy raising the siege of Mantua. He would soon retreat to Borgoforte and Marcaria, from where he would control the road to Cremona. Sauret remained at Desenzano. Guieu was still holding out at Salo against Quasdanovitch's left wing. Quasdanovitch continued his advance towards the Chiese, reaching Ponte San Marco and Montechiaro [Montichiari] .

On the night of the 30th and 31st, Masséna and Augereau crossed the Mincio, leaving a few troops behind. The former headed for Lonato, the latter for Montechiaro. Bonaparte himself headed for Desenzano , where he ordered General Sauret to rescue General Guieu. Sauret carried out the order, and the following day positioned himself between Salo and Desenzano.

On the 31st, General Despinoy, who was being mistreated at Lonato, was rescued by Napoleon Bonaparte at the head of the Rampon and Dallemagne brigades, drawn from the Masséna division. With their numerical superiority shifting sides, the Austrians were forced to retreat after losing 5-600 men. After these two setbacks, Quasdanovitch realized that he was facing the bulk of the French troops and retreated as far as Gavardo.

Bonaparte continued west towards Brescia with the Augereau and Despinoy divisions. Contrary to his expectations, the Austrians were barely in a position to challenge him for the town. He easily overcame their feeble resistance, expelled them, and left the Despinoy division behind. On August 2, he returned to Montechiaro.

In the east, Wurmser entered Mantua on August 1. He sent part of the garrison in pursuit of Sérurier towards Marcaria and Borgoforte, and deployed along the Mincio, placing his vanguard at Goito, under the command of Lipthay. After his successes at Rivoli and Salo, the traces of the French's hasty departure convinced him that his numerical superiority and strategy had given him a complete victory. He therefore remained more or less inert on the 2nd, content to advance Lipthay towards Castiglione delle Stiviere. The French rearguards on the Mincio were repulsed, in particular the troops occupying Castiglione, whose general behaved so badly that he was immediately dismissed. In the evening, Wurmser learns belatedly and with surprise of Quasdanovitch's violent attacks, the heavy losses inflicted on him, and his retreat to Gavardo. The delay in informing him was largely due to the position of the bulk of the French troops, who had managed to position themselves between the two enemy columns.

Austrian defeats

Battle of Lonato

On August 3, 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte, wishing to push Quasdanovitch even further back, entrusted General Despinoy, with 5-6,000 men, with the mission. His orders were to advance on Gavardo, Pietro [probably Chiesa S. Pietro, 45.62120, 10.49128] and Salo in three columns, with a fourth column threatening the Austrians' right flank through Osetto [probably Soseto]. Augereau, reinforced by Kilmaine's cavalry, was charged with retaking Castiglione. Bonaparte himself remained with Masséna at Lonato , in the center of the system, ready to move wherever circumstances required.

Despite stubborn resistance from Lipthay, Augereau managed to establish himself at Castiglione. On the other hand, facing Quasdanovitch, Despinoy was outnumbered and driven back to Rezzato and Brescia, with only General Guieu, on the right wing, managing to advance as far as Salo. The Austrians reached Lonato, where they defeated General Jean Joseph Magdeleine Pijon (or Pigeon), then advanced to Ponte San Marco. Here, they suddenly found themselves at odds with the Masséna division and Napoléon Bonaparte himself, who had just arrived. The Austrians tried to overrun on both flanks, but their own center was pushed in and their wings separated. Quasdanovitch's troops finally rallied around Gavardo. Napoleon Bonaparte, who had remained in Lonato, sent reinforcements to Guieu and ordered Despinoy to attack again, still against Quasdanovitch.

In all, the day cost the Austrians 3,000 men and 20 artillery pieces. Although not decisive, the battle enabled the French to tackle future engagements in the best possible conditions. Firstly, Quasdanovitch was now virtually incapable of taking part, especially as he would be attacked again the following day by Guieu and, threatened on his right at Gavardo, would soon retreat to Riva and then to the fortress of Rocca d'Anfo. Wurmser himself was not intact, and the French could now attack him with the advantage of numbers. If he evaded them, the pursuit into the mountains would give them the opportunity to treat him even worse. Napoleon Bonaparte therefore decided to march on Wurmser on August 5.

August 4 was devoted to refitting the troops and awaiting the approach of two brigades of the Sérurier division, commanded by general Pascal Antoine Fiorella, who had been ordered to move from Marcaria to Guidizzolo, where they were to be ready for action the following day.

Battle of Castiglione

On the morning of the 5th, Napoleon Bonaparte advanced on Solferino . Masséna was on the left, Augereau on the right, with Kilmaine behind him. Fiorella, who had arrived at Guidizzolo at dawn, was ordered to march on Cavriana , behind the Austrians. This represented a total of around 30,000 men. Wurmser had 29,000. His right wing was at Solferino, his left positioned across the road from Brescia to Mantua . Attacked both from the front and from behind, Wurmser had to retreat to Valeggio sul Mincio and Peschiera , but managed to limit the damage thanks to his superior cavalry. Nevertheless, he lost 3,000 men and twenty cannon. After the battle, the French pursued him only as far as Pozzolenzo and Castellaro Lagusello .

Wurmser initially tried to hold on to an entrenched camp near Peschiera, but Masséna dislodged him on August 6. Now too weak to hold the Mincio or even to remain too closely in contact with the French army, he renewed and reinforced the Mantua garrison, bringing it up to 15,000 men, then moved up the Adige valley and the Tyrol.

He was initially followed by almost the entire French army. But Sérurier soon turned back to recapture Verona and reposition himself in front of Mantua. On August 7, Masséna returned to his former position at Rivoli Veronese , before occupying Monte Baldo and La Corona on the 11th. Augereau moved back to the plain. West of Lake Garda, Limone and Riva fell, along with the important Rocca d'Anfo post in the Idro valley, on the 12th.

Quasdanovitch rejoined the main Austrian army near Ala, in the Adige valley, after which Wurmser returned to Trento , leaving his vanguard at Rovereto.

In Mantua, the French once again contented themselves with a simple blockade of the city, as they lacked any siege apparatus. All available equipment had been destroyed during Wurmser's offensive. Reconstituting it would be impossible in the short time available to take the city before the next Austrian attack, which was known to be imminent. Bonaparte therefore deemed it pointless to risk losing his equipment again when the next attack came.

Results of the offensive

Paradoxically, at the end of this unsuccessful offensive, the situation, while not very different from that at the end of June 1796, had actually improved from the Austrian point of view. Although almost constantly defeated, Wurmser nevertheless succeeded in preventing the capture of Mantua and even stopped the siege of the city. The French, still victorious, failed to achieve the decisive victory that would have enabled them to pursue their enemies across the Tyrol, and were held back in Italy by the defensive value of Mantua.

Operations were interrupted until early September 1796. The reason for this inaction was the shortages of all kinds suffered by French troops, and the expectation of 20,000 reinforcements from the Ocean Coast and Alpine armies, which the French government had promised Bonaparte. These soldiers were essential to him, as his army had 15,000 sick men in its ranks.

A difference of opinion with the Directorate on the next steps to be taken undoubtedly also contributed to this temporary immobility. While Napoleon Bonaparte wanted to march on Trieste, destroy the city and its port, and threaten the center of Austria, the Parisian authorities repeatedly rejected this project, which was indeed very risky in strategic terms. They preferred a simple march on the Tyrol, to prevent Wurmser, who had been left to rest, from detaching troops to Germany, where Jean-Victor Marie Moreau and Jean-Baptiste Jourdan were now battling with the Archduke Charles of Austria.

Wurmser's second offensive

French positions

At the end of August 1796, the 45,000-strong French force was distributed as follows:

- 13,000 men at Rivoli, with Masséna ;

- 9,000 men at Verona, with Augereau ;

- 11,000 men on the western shore of Lake Garda with Vaubois, who replaced Sauret;

- 10,000 men in front of Mantoue, with Jean Joseph François de Sahuguet d'Amarzit de Laroche, who replaced Sérurier;

- 2,000 cavalry between the Mincio and Adige rivers, with Kilmaine.

New campaign plan and Austrian positions

The Austrians, for their part, had already reconstituted Wurmser's army and increased it to 45,000 men. The new plan, the brainchild of an engineer general named Franz von Lauer, again involved dividing the army. Paul von Davidovitch would remain in the Tyrol with 20,000 men; Wurmser would spread out into the plain via the Brenta valley. If the French army moves in front of the latter, a good-sized corps, removed from Davidovitch's forces, would advance behind the French through the Adige valley. The latter would thus be forced to retreat between the Adige and Mincio rivers, blocked in the plain and unable to enter the Tyrol, unless they preferred to give battle.

This plan, which Clausewitz considered even worse than the first offensive, was flawed by the fact that it targeted an objective of no major strategic interest, without really giving itself the means to achieve it, and at the cost of abandoning the security provided by the Alps. Mantua showed no signs of falling, Austrian forces were less well-stocked than in July, and Napoleon Bonaparte had already twice felt too weak to venture into the Tyrolean mountains.

Davidovitch's forces, whose HQ was in Rovereto , were divided between two secondary corps facing the Vorarlberg and Valtellina masifs, and a main corps of 14,000 men positioned around Trento. A division belonging to the latter was located south of Rovereto, at Mori , on the right bank of the Adige. It comprised 5,000 to 6,000 men and was commanded by Prince Heinrich zu Reuss-Plauen. Another, under Wükassovitch, was at San Marco [today Marco, not far from Rovereto] , with an advance guard at Serravalle. The reserve occupied a very solid position at Calliano.

Wurmser marched towards Bassano del Grappa through the Brenta valley with the Quasdanovitch, Sebottendorf and Johann Mészáros von Szoboszló divisions, 26,000 men in all.

Bonaparte's attack on Davidovitch

Faced with these movements, of which he was quickly informed, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to leave Kilmaine with 3,000 men on the plains of Verona and Porto Legnago to protect the blockade of Mantua, while he himself marched on the Alto Adige with Vaubois, Masséna and Augereau. After defeating Davidovitch, he would set off in pursuit of Wurmser to confront him wherever he could be.

With Davidovitch north of Lake Garda , Napoleon Bonaparte sent Vaubois up the western shore, while the other two divisions took the eastern shore. On September 3, Vaubois reached the bridge over the Sarca, near Torbole, took it and presented himself in front of Mori. Masséna, for his part, repulsed the Austrians from Ala and then Serravalle, and reached San Marco. Augereau followed as a reserve, securing the ridges.

On September 4, Vaubois and Masséna attacked the villages of Mori and San Marco, chasing the Austrians through Rovereto to Calliano . Reached in the afternoon, the position, though very strong, was taken before nightfall. The Austrians withdrew to Trento with a loss of 3,000 men. The following day, Masséna entered the town, while Vaubois attacked Davidovitch again in the evening. Installed at Lavis, a few kilometers north of Trento, behind the Avio, he was still too close to the entrance to the Brenta valley for Napoleon Bonaparte's liking. He was therefore pushed back to Neumarkt.

Once again, Napoleon Bonaparte's strategic dispositions enabled him to attack the Austrians with a strong numerical superiority. Davidovitch's strength in these battles was estimated at around 10,000 men, while the Vaubois and Masséna divisions total around 20,000.

Bonaparte in pursuit of Wurmser

On learning of these events, Wurmser decided not to turn back, but to continue towards Verona and Mantua, in order to force the French back down onto the Italian plain. However, far from retracing his steps, as the Austrians had expected, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to follow them down the Brenta valley with the Masséna and Augereau divisions, totalling 20,000 men. Vaubois alone remained on the Avio to keep an eye on Davidovitch.

By September 7, Augereau was in Primolano, forcing the surrender of three Croatian battalions left behind by Wurmser. 1,500 men and 5 cannons fell to the French. That same day, Wurmser took up position with Sebottendorf and Quasdanovitch on a plateau near Bassano del Grappa. His headquarters were in Bassano itself . A few troops posted at Campo Lungo and Sologna, on either bank of the Brenta, covered the army's rear. The vanguard, under Mészáros, advanced towards Montebello Vicentino.

Attacked on the 8th, the rear-guard detachments finally took refuge in the Austrian camp and the town of Bassano, after offering sufficient resistance to give the main army time to make its dispositions. These arrangements, if any, did not prevent the French from seizing not only the town but also large quantities of equipment. The Austrian army was cut in two. More than 2,000 prisoners and 30 cannons were left behind, perhaps even without a fight.

Separated from the main Austrian corps, Quasdanovitch rushed off in the direction of Friuli. Wurmser fled to Fontaniva. He crossed the Brenta that same day and headed for Vicenza, then on to Montebello Vicentino and Legnago, with the intention of locking himself in Mantua with his remaining 12,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.

Also on September 8, Napoleon Bonaparte sent Augereau to position himself on the Padua road, to cut off Wurmser's route to Friuli. At the same time, Masséna left for Vicenza, arriving there at dusk and leaving the next morning for Ronco. He crossed the Adige on the 10th on rafts. On the morning of the 11th, he reached Sanguinetto, having covered almost 200 kilometers in six days, taken part in the battle of Bassano and crossed the Adige by makeshift means.

The aim of all these movements was to obtain Wurmser's surrender. Napoleon Bonaparte believed that the nature of the terrain, dotted with marshes and rivers between Legnago and Mantua, and the crossing of the Adige, would slow down the Austrians sufficiently for Kilmaine to have time to rush to Wurmser's front, while Masséna and Augereau attacked him from the rear and flanks.

Wurmser in Mantua

Wurmser passed through Legnago on September 10, leaving 1,800 men and 20 cannons behind, then continued his march towards Mantua. He crossed Sanguinetto on the 11th, after victoriously contesting possession of the bridge over the Menago with Masséna's vanguard. A night march brought him to Nogara on the 12th. A weakly defended passage to Villa Impenta enabled him to cross without difficulty the cordon of French troops blocking Mantua, where he arrived without further hindrance.

Masséna reached Castel D'Ario on the 12th, but too late to intervene. On the 13th, he moved on to Due Castelli [Castelbelforte]. Also on the 12th, Augereau surrendered the Austrian garrison at Legnago, then took Mantua on the Governolo side.

Now with 29,000 men, including 4,000 cavalry, Wurmser had no intention of allowing himself to be confined to the town itself, and set up camp between La Favorite and San Giorgio Mantovano. Masséna tried to surprise him there on the 14th, taking advantage of a possible laxity following the installation. He was rather curtly driven back to Due Castelli.

The series of victorious battles that the Austrians had experienced in the last days of the retreat led Wurmser to attempt a larger-scale attack on September 15, without any real strategic necessity. On that day, he advanced between the Verona and Legnago roads with 16-18,000 men. But the Masséna and Augereau divisions (the latter, ill, was replaced by General Louis André Bon) pushed him back between the Citadel and Fort San Giorgio, which General Victor took. Wurmser had to bring all his men back to the fort, not without difficulty, via the Citadelle road. He had lost almost 2,000 men in the adventure, and now held only the Citadel on the left bank of the Mincio. On the right bank, he retained control of the Serraglio, a highly fertile area bounded by the Mincio, the Po and the canal from Mantua to Borgoforte.

The garrison, plagued by disease, numbered around eighteen thousand able-bodied men, with whom Wurmser would attempt numerous unsuccessful sorties over the following months.

As the Directorate considered a siege pointless, since Mantua could only fall due to famine and epidemics, the town was once again subjected to a simple blockade, using only 9,000 soldiers, now led by Kilmaine. The remaining 33,000 were divided between Verona, Bassano and Trento, with the reserve at Villafranca di Verona.

Results of the offensive

The offensive failed completely this time. The Austrian situation was much worse in mid-September 1796 than before the offensive. Not only had Mantua not been liberated, but the city now contained a double garrison, threatened by famine. Once again, Bonaparte made perfect use of his enemies' mistakes. The first was not only to divide their forces, but to separate the two bodies thus created by mountains offering only a single communication route. Once this was in French hands, the division of the Austrian army proved irremediable. What's more, Bonaparte completely surprised his adversary by not returning down the Adige valley once Davidovitch had been defeated, and by pursuing Wurmser through the Brenta valley. As a result, in order to avert any danger from Davidovitch, he had to leave a large body of troops in front of the latter, thus accepting that this time he had only a limited numerical superiority over his adversary. In return, however, he gained the advantage of being able to pursue his offensive without giving his enemy a moment's pause, and by rushing to his rear. As Clausewitz wrote: (...) He (Bonaparte) chose the most decisive solution (...) and he carried it out with a dizzying vigor and speed, the like of which has never been equaled.

For the next few months, Napoleon Bonaparte remained more or less immobile in his positions. There were several reasons for this pause. Firstly, with Wurmser's entry into Mantua, the surrender of the city would now be tantamount to the capture of an entire Austrian army, and became a sufficient objective in itself for an army the size of Bonaparte's. Secondly, the political situation on the Italian peninsula had changed.

The political situation on the peninsula was another good reason not to venture beyond the Alps. By favoring the local Republicans, the French made it easier for themselves to manage the occupied territories, but they also stirred up hatred among the other parties. Any major setback could provoke new uprisings comparable to those suppressed in Milan in May. Relations with the court in Turin were not characterized by confidence. Piedmont continued to maintain underhand contacts with Vienna, and the French Directory could not bring itself to make sufficient proposals to draw it into the French orbit. The government of Genoa was not in the best of dispositions towards France either; Milan was giving cause for concern; the King of Naples was not far from being on a war footing, and the Pope was making preparations to enter the conflict. If the latter two manage to equip a few tens of thousands of men and coordinate their attack with a new Austrian offensive, the French position in Northern Italy will become more than precarious. There was therefore no question of inciting them to act by rashly moving towards the Austrian border in an operation that would mobilize the bulk of the Republic's forces.

However, concerns about Naples eased in October 1796, when negotiations between the kingdom and the French Directory, which had been languishing during the operations, resumed in earnest following the defeats of Wurmser in Italy and Jourdan in Germany. Now more cautious than ever, the two sides came to an agreement and signed a peace treaty on October 10. Napoleon Bonaparte nevertheless persisted in his attitude, devoting most of his time to politics and administration, while busy restoring his army and rebuilding its equipment.

Alvinczy's first offensive

The new Austrian plan

Meanwhile, Austria, whose situation in Germany had improved considerably, took steps to come as quickly as possible to the aid of Wurmser, whose troops were beginning to suffer from deprivation in Mantua. By mid-October, just four weeks after the last battles of the previous offensive, Quasdanovitch's force, which had returned with 6,000 men to the Piave and Isonzo rivers, had increased fivefold. Davidovitch, in the Tyrol, also strengthened his position, among other things by recovering the troops rendered useless by Moreau's retreat from Vorarlberg. He now had 20,000 soldiers.

The plan again called for a two-column attack, but this time the arrangement was a natural consequence of the way the forces were organized, with Quasdanovitch in Friuli and around Bellune, and Davidovitch in Tyrol.

The planned maneuver was as follows: Quasdanovitch would cross the Piave to advance on Bassano, his right flank covered by Davidovitch, who would capture Trento and Calliano at the same time. Thus protected, the corps from Friuli would advance through Vicenza to the Adige and Verona, where it would attack the French army. Davidovitch, for his part, would do his utmost to link up at least some of his troops with those of Quasdanovitch, either through Val Freddo or the Adige valley. Finally, Wurmser was to be ready to make a sortie to the rear of the French army when it was engaged in the planned battle near Verona. A new general-in-chief, Josef Alvinczy von Borberek, was appointed to direct the maneuver. He ordered a simultaneous attack on Bassano and Trento on November 3, but did not intend to cross the Adige until Davidovitch had announced that the valley was free of enemies.

French positions

On this date, the French occupied the following positions:

- Vaubois at Trento with 10,000 men;

- Kilmaine in front of Mantoue with 9,000 men;

- Augereau at Verona with 9,000 men;

- Masséna at Treviso and Bassano with 10,000 men;

- 4,000 reserve men at Villafranca.

Davidovich's initial successes

To avoid a possible junction between Davidovitch and Alvinczy through the Brenta valley, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered General Vaubois to push back the Austrian outposts on the Avio. The attack took place on November 2 at two points: Saint-Michel, where Guieu was successful, and Segonzano, where Fiorella and Vaubois failed to repel Wukassovitch. On the contrary, it was they who were pushed back the next day when Davidovitch arrived with the bulk of his forces. They retreated as far as Calliano. Three days later, Davidovitch attacked them again, failing in front of the town but capturing the Nomi and Torbole posts. He pressed on on the 7th, taking Mori and pushing Vaubois back towards Rivoli and La Corona. His subsequent successes took him as far as Serravalle , where he stopped, despite inflicting heavy losses on the French and taking 6 cannons. He would now wait until November 16 for the outcome of Alvinczy's operations before opening up on the plain.

Alvinczy's advance

Alvinczy crossed the Piave on November 2. With Masséna having withdrawn to Vicenza on the 4th, only the French rearguards remained on the Brenta. They were repulsed. Alvinczy divided his army into two columns. The first, commanded by Quasdanovitch, advanced as far as Bassano. The second, under Provera, advanced as far as Citadella and even sent Lipthay as a vanguard to Fontaniva . Napoleon Bonaparte, informed of Vaubois' defeats, calculated that it would take the Austrians several days to drive his lieutenant from the mountains, and decided that he could attack Alvinczy in the meantime. Masséna was ordered to move on Fontaniva and Augereau on Bassano. While Provera covered the river both upstream and downstream, keeping his reserves at Citadella , Lipthay withdrew to an island in the old Brenta as the French approached. On the 6th, he engaged Masséna in a fierce battle, which appeared to be to Masséna's advantage. As for Augereau, he came up against Quasdanovitch's vanguard, on the march towards Vicenza, in the vicinity of Marostica . After a determined fight, Friedrich Franz Xaver von Hohenzollern-Hechingen, who commanded this detachment, withdrew to the solid position established by his commander between the Brenta and the first slopes of the Sette Communi. The Austrians held out until nightfall.

Worried about Vaubois, having failed to gain a decisive advantage against Alvinczy and seeing his line of retreat threatened if Masséna was repulsed by Provera, Napoleon Bonaparte abandoned his plan and withdrew to regroup his forces. On November 7, Masséna and Augereau returned to Verona via Vicenza and Montebello Vicentino , followed by Alvinczy. On the 11th, Alvinczy was at Villanova [San Bonifacio district], with an advance guard at Caldiero.

Napoleon Bonaparte had been in Verona since the 8th. He had learned that Davidovitch was still stationary at Serravalle. He therefore gave his troops two days' rest before resuming hostilities against Alvinczy. On the 11th, the Austrian vanguard was repulsed with losses after attempting an incursion at Saint-Martin and Saint-Michel, at the gates of Verona. Towards Caldiero, it rallied an Austrian force of 8,000 men occupying an extremely secure position around the town. The right wing reached the village of Colognola, at the foot of Monte Oliveto, while the left wing reached the steep escarpments behind the village itself. The line that joined them was at the top of a gently sloping hill. Alvinczy intended to hold this position long enough for the rest of his troops to surprise the French army, which was in the process of assaulting it, with a flanking movement.

On November 12, everything went according to plan: the French attacked; Augereau, on the left, took the village of Caldiero; Masséna, on the right, that of Colognola; Alvinczy's army then emerged and took the lead over the attackers. Although the French army lost 2,000 men, the morale of both troops and commanders did not seem to suffer. All the more so as the Austrians, without seeking to exploit their advantage, allowed the French to retreat quietly to San Giacomo and then, the following day, to their camp under Verona.

Bonaparte's new arrangements

Bonaparte came up with a new plan. He was going to break free on the right, cross the Adige at Ronco and surprise the Austrians' left flank, either in their position at Caldiero, in their march on Verona, or in their crossing of the Adige, depending on what they would have undertaken. However, 24 hours elapsed before this project was carried out. Some authors explain this delay by the indecision resulting from the dangers of the situation. Clausewitz considered this interpretation incompatible with Bonaparte's character, preferring to attribute the delay to unknown external causes.

Nevertheless, on the evening of November 14th, the French set off on their march, crossing the river at dawn on the 15th. Alvinczy, who had advanced as far as Saint-Martin the previous day, bringing him closer to Verona as Bonaparte had hoped, planned to cross the Adige at Zevio with half his army, while the other half would attack Verona. This move, excessively audacious when the enemy army was so close, was to begin on the night of the 15th to the 16th, but was abandoned on the news of Bonaparte's crossing of the Adige. The next three days were occupied by the various battles and tactical movements that made up the Battle of Arcole, which ended with Alvinczy's retreat. Although both armies suffered similar losses, the Austrian general-in-chief no longer felt up to the decisive battle that Bonaparte was likely to force upon him on the plains on the 18th if he persisted. This time, Napoleon Bonaparte was able to get out of a tricky situation thanks to better management of partial battles, greater resolve, unparalleled audacity and troops of exceptional calibre.

Austrian retreat

Meanwhile, Davidovitch was back on the move. On November 16, he drove Vaubois and his 6,000 men from the Corona, on the 17th from Rivoli, and on the 18th from Castelnovo, driving them back behind the Mincio. Aware of these defeats, Napoleon Bonaparte, after Arcole, simply sent his reserve cavalry in pursuit of Alvinczy and immediately turned against Davidovitch. He had Masséna march on Villafranca, where Vaubois was to withdraw, and sent Augereau to cut off the Austrians' retreat to the Adige valley, via Verona, Monte Molare and Dolce. But Davidovitch realized in time the danger he was in. He withdrew to Ala on the 19th, but his rearguard suffered heavy losses at Campara. Alvinczy, who had in the meantime reached Montebello Vicentino, in turn sent a few detachments to threaten Augereau's flank at Monte Molare, and returned to Villanova himself on the 20th to reinforce this threat. Napoleon Bonaparte reacted by returning to Verona, and Alvinczy withdrew behind the Brenta, his left wing to Padua, the right to Trento. Bonaparte resumed the same position on the Adige as before the Austrian offensive. A final attempt to extricate Wurmser on the 23rd, far too late, produced no results.

Political interlude

Peace reigned in Italy for the next two months. As after Bassano, the French had the best reason in the world to concentrate on blockading Mantua, while the Austrians were once again busy reinforcing their army, which was once again increased to around 40,000 men.

In the meantime, Napoleon Bonaparte returned to his preoccupations with Italian politics, gradually emancipating himself from Parisian tutelage. In France, the Directorate, in its desire to achieve peace, did not want to work for the independence of Italian conquests, which it intended to use as a bargaining chip with Austria to retain Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine. The same reason led him to forego the alliances of Piedmont and Parma, which he considered conditional on the cession of part of the conquered territories. Napoleon Bonaparte's analysis was different. Far less committed to the quest for peace, and although aware of the usefulness of the contingents that Piedmont, Parma and Venice could provide, he nonetheless believed that an agreement with these states could be envisaged at the price of a simple guarantee of their borders and a muffling of Republican ventures in their territories. He was therefore not afraid to push for the creation of republics in the remaining provinces under his control. The territories of Bologna, Ferrara, Reggio and Modena formed a Cispadane Republic. The proclamation of a Lombard republic was prevented only by strong opposition from the French Directory.

General Henri-Jacques-Guillaume Clarke arrived in Italy, en route to Vienna to deliver the Directorate's peace proposals. The Emperor of Germany, while refusing to receive him under the pretext of talks already underway with the French Directory via the English ambassador to France, nevertheless sent a plenipotentiary to discuss a possible armistice. But while Clarke leaned towards an agreement confirming the status quo, Napoleon Bonaparte was opposed to any settlement that did not include the surrender of Mantua, an essential condition if it was not to be totally favorable to the Austrians. Discussions in Paris failed on November 19, with neither England nor Austria seriously committed to reaching an agreement. Those in Italy were soon interrupted by Alvinczy's new offensive.

Alvinczy's second offensive

French positions

By this time, Napoleon Bonaparte had received a number of reinforcements, bringing his strength to 47,000 men, distributed as follows:

- Joubert at Rivoli with 10,000 soldiers;

- Masséna in Verona with 9,000 ;

- Sérurier in front of Mantoue with 10,000 ;

- Augereau around Legnago with 9,000 ;

- Gabriel Venance Rey at Desenzano with 4,000 ;

- Lannes at Bologna with 2,000 ;

- Victor and a reserve of 2,000 men at Goito;

- Plus a small cavalry reserve of 700 horses.

4th Austrian plan to deliver Mantua

This time, the Austrians could only muster 45,000 men, 42,000 of whom were available for the attack. Their plan was similar to the previous one, except that the main column was to attack Rivoli Veronese, under the command of Alvinczy. Two other columns would arrive from the plain. The first, of 5,000 men, under General Adam Bajalics von Bajaháza (Bayalitsch), was aimed at Verona. The second, with 9,000 men under Provera, advanced through Padua towards Legnago. The main purpose of these two columns was to hold back the bulk of the French forces on the plains, while the Joubert division was destroyed by Alvinczy in the mountains. They were also to head steadily towards Mantua to rescue Wurmser, who would by now have received a letter informing him of the arrangements to be made. Unfortunately for him, the bearer of these orders was intercepted by the French. The Viennese court also sent the Pope Austrian generals and officers to supervise the 15,000 men equipped by the Holy Father. The hope was to keep 5,000 to 6,000 Frenchmen away from the theater of operations. But Napoleon Bonaparte considered it sufficient to leave a thousand of his own soldiers, supported by 4,000 Lombards, in front of these troops. Once again, he concentrated his forces on the main objective, without scattering them over secondary theaters of operation.

The operations

On January 7 and 8, 1797, Provera's vanguard under Hohenzollern came up against Augereau's vanguard near Bevilacqua. On the 9th, the main part of the column arrived in front of Legnago. On the 12th, Bayalitsch appeared in front of Verona.

On the same day, the main attack on Joubert's position took place. Joubert occupied Coronna and, a little further south, Rivoli Veronese . The terrain was laid out in such a way as to allow the defender to bring in detachments of all weapons, while the attacker could use almost only his infantry. The attacker had therefore to enjoy a significant numerical superiority if he was to win, but if he did, the result was virtually assured. Joubert had 10,000 men, while the Austrians brought 22,000. Alvinczy also knew that Napoleon Bonaparte was not there, but in Bologna, where he was busy organizing the Cispadane Republic. Finally, the Austrian general hoped to divert his adversary's attention and cause him to ignore the critical point of the attack, by sending columns towards Legnago and Verona. Having weighed up all these circumstances, Alvinczy felt he had enough time not only to defeat Joubert, but also to surround him in such a way that all he had to do was lay down his arms.

The Austrians therefore divided their army into six columns to assault Rivoli Veronese from all sides. The first, commanded by colonel Franz Joseph de Lusignan, was to take the position from the rear through Pezzena [Pesina]. The second, under Lipthay, and the third, under General Samuel Köblös de Nagy-Varád, passed through side valleys to reach La Corona head-on and on the left flank. The fourth, under Quasdanovitch, advanced along the right bank of the Adige and climbed to the Rivoli plateau via the Osteria [Zuane Osteria] defile. The fifth, under Joseph Ocskay von Ocskó, followed as a reserve, with the mission of supporting Quasdanovitch, Köblös or Lipthay, depending on circumstances. The sixth, under Wükassovitch, marched along the left bank of the Adige to capture the post of La Chiusa and control the rear of the Rivoli position.

All these columns, the first three of which were virtually devoid of both artillery and cavalry, set off on January 11th and attacked La Corona on the morning of the 12th. Coordination problems between the various detachments hampered the Austrian operations, and Joubert managed to hold his position throughout the day. However, at 4 a.m. the next day, on learning that Lusignan was maneuvering to catch him from the rear, he withdrew in good order to Rivoli Veronese, where he remained until the evening. The Austrians, who were advancing very slowly, left him more or less alone, but positioned themselves to attack the following day.

By January 14th, the first Austrian column had moved to Lumini, the second and third columns were advancing on the villages of Caprino and San Martino , at the foot of Monte Baldo ; the position of the other three is unknown to us. Joubert, observing these movements and seeing all the surrounding ridges crowned with Austrian fire while he himself received no news or reinforcements, decided at around ten o'clock in the evening to retreat towards Villanova via Campara to avoid being surrounded and crushed by forces far superior in numbers to those at his disposal. He had just set off on his march when he simultaneously received the news that Bonaparte was about to join him and the order to hold out in front of Rivoli. He immediately carried out the order and retraced his steps.