Battle of Berezina

Date and place

- November 26th to 29th, 1812 near the Berezina River (now Belarus).

Involved forces

- French army: 49,000 combatants under the command of Emperor Napoleon I

- Russian army under Tzar Alexander I, Generals Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov and Peter Wittgenstein, and Admiral Pavel Vasilievich Chichagov.

Casualties and losses

- Grande Armée: 25,000 fighters, 10,000 to 30,000 stragglers.

- Russian Army: more than 20,000 soldiers.

The Battle of Berezina stands as the only example of a victory whose name has paradoxically entered common parlance as a synonym for disaster or rout.

General situation

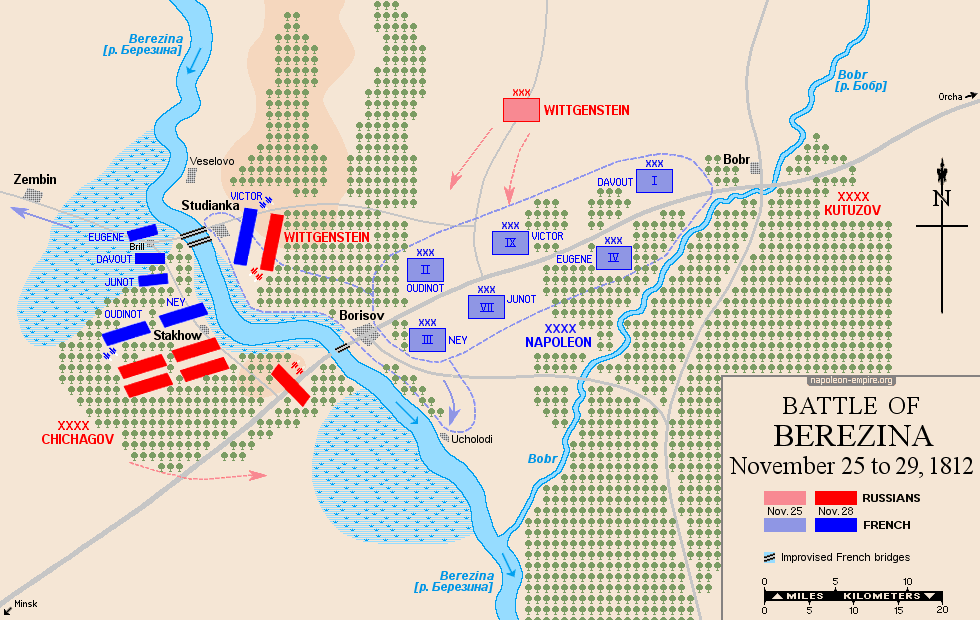

Five weeks after leaving Moscow, the Grande Armée continued its retreat following the disastrous French invasion of Russia. The fall of Minsk to the Russians forced it to divert towards the Berezina [Бярэзіна], a marshy river, a tributary of the Dnieper. Marshal Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov (ММихаил Илларионович Голенищев-Кутузов) fully intended to exploit this natural obstacle in his adversary's path to annihilate him once and for all.

Since the Berezina River was not frozen despite the frigid temperatures, the town of Borisov [Барысаў] [54.245223, 28.50443] and its bridge had acquired strategic importance. French forces converged there:

- the Guard and the Corps returning from Moscow around Napoleon I:

- 1st (Marshal Davout);

- 3rd (Marshal Ney);

- 4th (Prince Eugène de Beauharnais);

- 5th (General Poniatowski);

- 8th (General Junot).

- The 2nd Corps, under the command of Marshal Oudinot;

- The 9th, under Marshal Victor;

- The Polish garrison driven from Minsk by Pavel Vasilievich Chichagov (Па́вел Васи́льевич Чича́гов) ;

- The division of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowsk.

Together, approximately 49,000 men, followed by 40,000 stragglers.

No fewer than three Russian armies were also heading towards this crucial crossing point for the French:

- The Army of the Center, under Marshal Kutuzov (70,000 men), was pursuing Napoleon from Moscow. Its main force was arriving from the southeast. Its vanguard, composed of the Cossacks of Matvey Ivanovich Platov and the reserve of Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich, was closing in on the French rearguard to the east;

- The army of General Pyotr Christianovich Wittgenstein (Пётр Христиа́нович Ви́тгенштейн) (30,000 men) was advancing from the north;

- The Moldavian army, under the command of Admiral Chichagov (35,000 men), was approaching from the southwest.

On November 21, 1812, Chichagov took control of Borisov. The situation of the French army appeared hopeless.

Forty-eight hours later, on the 23rd, the 2nd Corps reoccupied Borisov. Its adversaries withdrew to the opposite bank, where they established a strong presence after setting fire to the bridge behind them. Chichagov, like all the Russian generals, maintained a cautious wait-and-see approach in the following days. This passivity would render their maneuvers futile.

Construction of the Studianka Bridges

General Jean-Baptiste Juvénal Corbineau had indeed discovered a ford at Studianka [Студзёнка] [54.32604, 28.35336], a village located twenty kilometers north of Borisov. Despite its marshy banks, the riverbed appeared sufficiently narrow and shallow to allow for the construction of a bridge.

On Napoleon's orders, General Jean-Baptiste Éblé and his pontooners immediately set to work, despite the deadly water temperature and the presence of Russian campfires on the opposite bank. Sappers assisted them without entering the river.

Having abandoned most of their equipment ten days earlier at Orsha due to a shortage of horses, the French sourced the raw materials for the bulk of their work — horsestools and aprons — from the workshops at Studianka. The aprons were then covered with straw and hemp.

This flurry of activity provoked no reaction from the Russians. A diversionary maneuver orchestrated by the Emperor at Borisov, where Louis de Partouneaux's division feigned an attempt to cross and where Napoleon ostentatiously appeared on the 25th, completely misled Chichagov, diverting his attention away from the sensitive area.

Like the entire Russian command, he believed the French still intended to advance on Minsk to close the distance with General Charles-Philippe von Schwarzenberg's Austrian Corps.

It was the work being carried out at Studianka that the admiral viewed as a deception. Consequently, he moved his army south of Borisov, positioning his vanguard, led by General Yefim Ignatyevich Chaplits (фим Игнатьевич Чаплиц), fifteen kilometers south of Brili.

On the morning of the 26th, the French observed that the Russians had completely abandoned the right bank opposite Studianka. Forty cavalrymen immediately forded the river. Four hundred infantrymen joined them on rafts. Together, they secured the final section of the construction site.

Soon, two precarious footbridges, one hundred meters apart and the same length, spanned the Berezina River: the first, on the right (north, upstream), for the infantry; the second, on the left (south, downstream), more robust, for the artillery and vehicles. Napoleon did not leave the riverbanks during the construction, encouraging the workers and occasionally offering a bottle of wine to the most shivering among them.

Around 1 p.m., the French troops began crossing the Berezina. The 2nd Corps and Dombrovski's division crossed first. They were followed by Marshal Michel Ney's 3rd Corps and Prince Joseph Antoine Poniatowski's 5th Corps. Simultaneously, later in the afternoon, starting at 4 p.m., the artillery also began its crossing, which had to be interrupted several times due to the collapse of the trestles. Many drivers disregarded the recommendations and trot their horses, causing the river to sink.

The fights

November 27, 1812

On the 27th, on the right bank, Oudinot repelled detachments of the Russian General Chaplits. Chaplits attempted to regain a foothold at Brili after learning that the French were indeed crossing the river. Chichagov, observing no activity downstream from Borisov, approached the town but waited to assemble his troops before advancing further north.

Meanwhile, the crossing continued. The following crossed in succession:

- Napoleon and the Guard;

- Prince Eugène de Beauharnais's 4th Corps;

- Jean-Andoche Junot's 8th Corps;

- in the evening, Marshal Davout's 1st Corps, which had held the rearguard until then;

- various units, including the Daendels Division (26th Division, 9th Corps).

On the left bank, only part of Victor's Corps remained, notably the Partouneaux Division (12th). This division had been held at Borisov to neutralize the threat posed by Wittgenstein and Chichagov to the flanks of the French army. Its presence allowed the rearguard to withdraw in relative safety.

During the night, after holding his position until after the 1st Corps and the stragglers had passed, Partouneaux lost his way while trying to reach Studianka. Surrounded by Wittgenstein near Staroi-Borisov, he was forced to surrender, but not before having attempted a breakthrough during which the 126th Infantry Regiment was almost annihilated. For his part, Chichagov, realizing he had been tricked, rebuilt the Borisov bridge, thus securing the link-up with Wittgenstein.

November 28, 1812

On the morning of the 28th, in the snow, the Russians launched a coordinated offensive on both banks of the Berezina River.

The Emperor sent Daendels' division back to the left bank. It crossed the bridges with difficulty, against the flow of the crowd, to reinforce Victor's corps, which was bearing the brunt of Wittgenstein's attack. Ten thousand French and allied troops were tasked with holding back 30,000 Russians. They resisted valiantly, however, and retreated slowly. Cavalry General François Fournier-Sarlovèze launched repeated charges. A battery of the Guard, positioned on the right bank, bombarded the enemy.

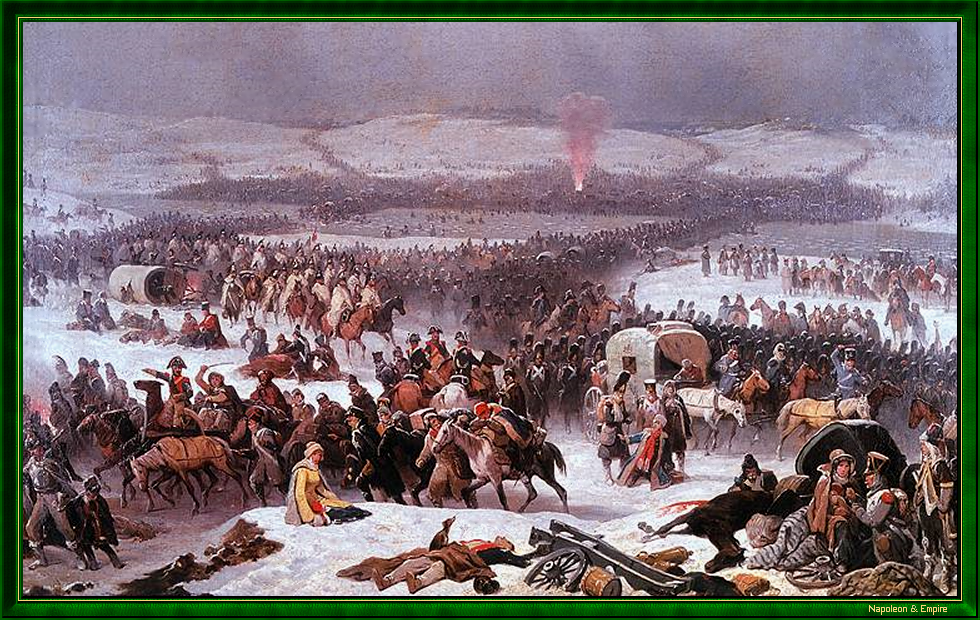

By 1:00 PM, Wittgenstein had advanced far enough to turn his artillery on the French stragglers and the bridges, causing panic. After a long battle, the 9th Corps finally crossed the river around 10 p.m., after the pontooners had cleared the approaches to the bridges, which were cluttered with dead men and horses.

On the right bank, Oudinot, soon wounded as usual, and then Ney, commanding 18,000 veterans, including 9,000 Poles, confronted the forces sent by Chichagov. Fatigue weighed heavily on both sides, as the Russians had also been exhausting themselves for three days in marches and countermarches.

The fighting was nonetheless fierce. The French infantry tenaciously defended its positions, supported by the artillery of the 2nd Corps. The Russians were ultimately driven back to the village of Bolshoi-Stakhow by a charge from the cuirassiers of General Jean-Pierre Doumerc — at least those whose horses hadn't already ended up as butcher's meat. Eugène and Davout's corps took advantage of the situation to advance on the road to Vilnius, protected by Marshal Adolphe Mortier's Young Guard.

November 29, 1812

When dawn broke on the 29th, almost all of the remaining organized troops had reached the right bank.

Eblé finally destroyed his work during the morning, having delayed as long as possible to give the stragglers a final chance to escape. Thousands, however, remained on the left bank. Most refused to leave their positions despite the warnings they had received. Some attempted to flee at the last minute by throwing themselves into the water or into the flames ravaging the bridges. The others were taken prisoner.

With Wittgenstein trapped at Studianka, only Chaplits was able to pursue the French marching towards Vilnius. But the French destroyed several bridges behind them, crucial for crossing the Gaina marshes between Brili and the Zembin road. Chaplits could not overcome this obstacle. The Grande Armée had escaped.

The outcome

The losses defied imagination.

They reached almost 25,000 French combatants, including the 4,000 men of Partouneaux's division. Their capture particularly angered Napoleon, as these were still relatively vigorous troops, having recently arrived in Russia. Their relative freshness would have been invaluable for the remainder of the retreat.

The 2nd and 9th Corps suffered the most: their numbers were halved. The Guard, which had not yet been engaged in combat, was reduced from 3,500 to 2,000 men. As for equipment, only twenty-five cannons were abandoned to the enemy.

To these already considerable figures must be added those of the stragglers, trapped on the left bank by their own apathy, whose number remains difficult to estimate. Estimates vary from 10,000 to 30,000 people, depending on the source. A large majority of them succumbed to hunger and hypothermia in the following days.

On the Russian side, the death toll and the number of wounded reached some twenty thousand, confirming the intensity of the fighting.

Aftermath

From a strictly military point of view, the crossing and the Battle of the Berezina represented successes for the French. They averted a seemingly inevitable catastrophe by finding a way out of the trap in which their adversaries believed they had cornered them.

The Russians, for their part, had missed a unique opportunity to crush the Grande Armée and perhaps even capture its commander. They knew it, and Chichagov would serve as a scapegoat for this failure. He would be relieved of his command, ostracized at court, and forced into exile in France before eventually becoming a British subject.

While the admiral had made mistakes, Marshal Kutuzov, who had failed to support his subordinates, also faced serious criticism.

From the French perspective, this hard-won success — a Pyrrhic victory if ever there was one — would nonetheless allow the remnants of the Grande Armée to continue their retreat. They would not see any further major engagements during the following month, but would endure constant and deadly harassment from the Cossacks. Added to this was a cold more intense than ever. So much so that on December 26, when they crossed the Niemen and left Russian soil for good, only a few thousand exhausted men remained.

In the longer term, the Battle of Berezina ensured the survival of a core of veterans, a number of officers and generals, two hundred cannons, and Napoleon himself. These would form the foundation upon which the Emperor would rebuild, starting the following year, an army capable of challenging the Sixth Coalition for victory.

Map of the battle of Berezina

Picture - "Przejscie wojsk Napoleona przez Berezyne - Napoleon crossing the Berezina River". Painted in 1866 by January Suchodolski.

General Eblé's pontooners, who heroically dedicated themselves to saving the Grande Armée, were mostly French, but also included Dutch and Polish soldiers. Most of them lost their lives in this Herculean task. Only six survived the retreat. Eblé himself died of exhaustion in Königsberg on December 31, 1812.

The renowned Soviet historian Eugène Tarlé, a fervent eulogist of the "Patriotic War" of 1812, considered Napoleon's crossing of the Berezina River one of his finest feats of arms.

This dramatic episode of the Russian campaign deeply moved writers: Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo, and Leon Tolstoy, to name only the greatest, found inspiration in it.

Despite the victory, the scale of the losses suffered made the name of this river synonymous with disaster or catastrophe in the French language.

Calendar

All dates on this page are in the Gregorian calendar (then twelve days ahead of the Julian calendar in use in Russia at that time).

Poem about the battle

In order to offer visitors a unique and innovative auditory experience, we have set this poem to music, with the help of the artificial intelligence software Suno.GIESECKE, Karl Ludwig (Augsburg 1761 - Dublin 1833)

"Beresinalied" - Published in 1792 under the name "Die Nachtreise"

The last four stanzas of Giesecke's poem, alternating between octosyllabic and heptasyllabic lines, were popularized under the title Beresinalied after being sung by Swiss soldiers of the II Corps during the battle of the Berezina. Becoming a symbol of the sacrifices of Swiss mercenaries in the service of the Grande Armée, this folk song has since become very well known throughout the Swiss Confederation, primarily in the version set to music in 1832 by Johann Immanuel Müller (1774-1839). It is a radically different version that we offer you.

Version set to music in 2026:

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.